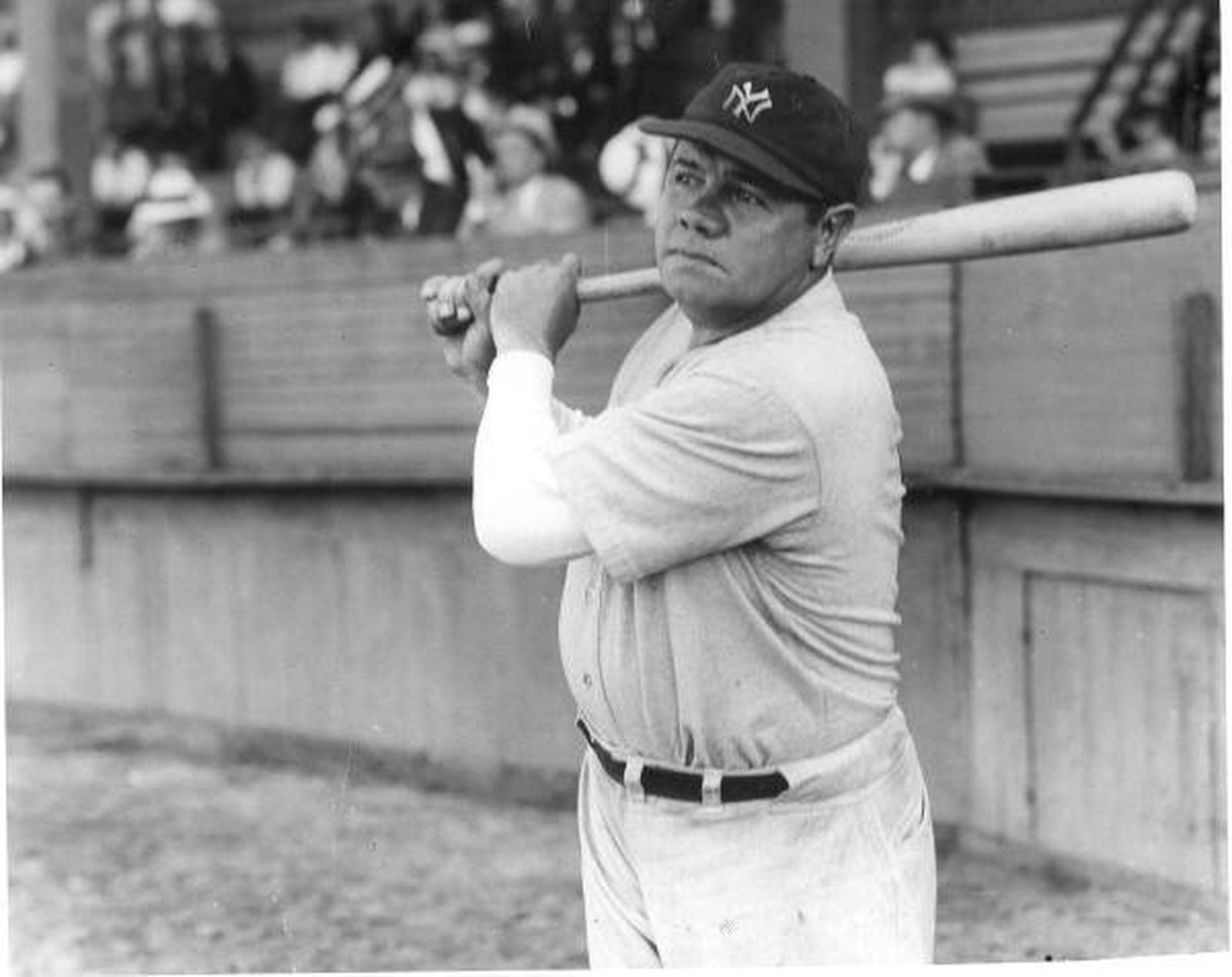

Among the many stories racked up about Babe Ruth is one told by Fred Lieb of the New York Telegram during spring training in Jacksonville, in his first year with the Yankees. A crippled boy lying on the backseat of his father’s open car, was propped up with pillows so he could watch the players. The Babe trotted up, waved, and called out, “Hiya keed,” as he passed by. To his father’s astonishment, his son stood up by himself to keep sight of Ruth as he ran into the clubhouse.

This is not to say that Babe Ruth was always a saint. His first wife, Helen Woodford, ended their marriage in 1925, citing Ruth’s infidelity and neglect. Tragically, she died in 1929. Ruth then married Claire Merritt Hodgson.

In a 2019 article, Gabriel Costa wrote:

It seems that the Yankees were on a road trip and Ruth arrived at the hotel early one Sunday morning, presumably after a night of carousing. He made sure all the Yankees who were Catholic were roused out of their beds to accompany him to an early Mass. During the sacred liturgy, as the collection basket was passed around, the Babe put in a $50 bill. When Tony Lazzeri realized what Ruth had done, he said — non sotto voce — “What are you doing Babe, paying for last night’s sins?”

In June 1926, the 28th International Eucharistic Congress took place in Chicago, the first time it was being held in the United States. At the same time, the Yankees arrived for a four-game series with the White Sox. Miller Huggins, the Yank’s beleaguered manager, was inspired to ask Bro. Matthias Boutlier, Ruth's mentor, to join them, all expenses paid, to see if he might talk to Ruth about his roistering while attending the Congress.

Bro. Matthias warmly greeted George when they met in the hotel lobby and went out to dine. The good brother let his former pupil know how disappointed he was, reminding George that, on the bases, he was a hero to the boys at St. Mary’s and across the nation, but, with his overindulgence, women and parties, he was setting a poor moral example for them. Ruth was properly chastened.

About this incident one of Ruth’s biographers, Marshall Smelser, wrote, “This was the turning point in Ruth’s behavior. Certainly he no longer after that time had the reputation for hell-raising that he had before.”

During the 1926 World Series, the Babe received an urgent telegram from New Jersey. A boy named Johnny Sylvester had been kicked in the head by a horse earlier that summer. His condition had worsened into osteomyelitis, a condition caused by an infection leading to bone deterioration. It was thought that a note from Ruth would strengthen his will to live.

The Bambino sent Johnny two baseballs, signed by all the Yankees and bearing his promise, "I'll knock a homer for you on Wednesday," in Game 4 of the series. The Sultan of Swat hit three homers that day, and newspapers reported that Johnny's condition had miraculously improved.

After retiring from active play in 1935, Ruth was disappointed in that he was never really considered for a managerial position, although he did coach for a season with the Brooklyn Dodgers. His uniform number, 3, was not retired by the Yankees until two months before his death, Babe thanking the fans at Yankee Stadium in a rough subdued voice, since he was dying from throat cancer.

In his final years, the Babe turned more and more to God, writing, “As I look back now, I realize that knowledge of God was a big crossroads with me. I got one thing straight (and I wish all kids did) — that God was Boss. He was not only my Boss but Boss of all my bosses.”

1948’s The Babe Ruth Story, starring William Bendix, features a scene toward the end about a boy and a medal. It is so very schmaltzy I was sure it was the invention of the screenwriters. But, no, here’s what the Babe had to say about the incident in his autobiography:

In December, 1946, I was in French Hospital, New York, facing a serious operation. Paul Carey, one of my oldest and closest friends, was by my bed one night.

“They’re going to operate in the morning, Babe,” Paul said. “Don’t you think you ought to put your house in order?”

I didn’t dodge the long, challenging look in his eyes. I knew what he meant. For the first time I realized that death might strike me out. I nodded, and Paul got up, called in a Chaplain, and I made a full confession.

“I’ll return in the morning and give you Holy Communion,” the chaplain said, “But you don’t have to fast.”

“I’ll fast,” I said. I didn’t have even a drop of water.

As I lay in bed that evening I thought to myself what a comforting feeling to be free from fear and worries. I now could simply turn them over to God. Later on, my wife brought in a letter from a little kid in Jersey City.

“Dear Babe,” he wrote, “Everybody in the seventh grade class is pulling and praying for you. I am enclosing a medal which if you wear will make you better. Your pal, Mike Quinlan.

P.S. I know this will be your 61st homer. You’ll hit it.” I asked them to pin the Miraculous Medal to my pajama coat. I’ve worn the medal constantly ever since. I’ll wear it to my grave.

Raised over the tombs of George and Caire Ruth at Gate of Heaven Cemetery in Hawthorne, N.Y., is a large marble tablet bearing a bas relief depicting Jesus blessing a small boy wearing knickers. It is accompanied by a prayer inscribed into the stone, originally composed for the Babe’s Requiem Mass by Francis Cardinal Spellman, then-archbishop of New York: ”May the Divine Spirit that animated Babe Ruth to win the crucial game of life, inspire the youth of America.”

One last feature should be mentioned. At the grotto in Lourdes where the Virgin Mary appeared, there used to hang hundreds of crutches left by those who felt cured by the miraculous spring there.

In the case of George Herman Ruth, Jr., on either side of the monument lean a number of baseball bats; in front of it is a pool of baseballs, tokens of affection left by fans still touched by the Great Bambino.

Sean M. Wright, MA, award-winning essayist, Emmy nominee, and Master Catechist for the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, is a parishioner at Our Lady of Perpetual Help in Santa Clarita. he answers comments at Locksley69@aol.com.