On Sunday, Aug. 22, the Gospel reading is the last of the five excerpts taken from St. John’s account of the good news, interrupting the flow of the Gospel of St. Mark in Cycle B. For the past month, the readings at each Sunday Mass have focused on Jesus’ “Bread of Life” discourse.

To summarize, the first excerpt showed on how Jesus fed 5,000 men (the number not including any women or children present) with five small barley loaves and two fishes. This was certainly the dried fish, salted for preservation, commonly eaten in Galilee.

The next segment describes what happened the following day. Confronted by the crowd looking for more free food, as Moses had fed their ancestors with manna, “bread from heaven,” Jesus corrects them, explaining that God, his Father, had sent the manna. Even so, the manna is not the real bread from heaven. He is the Bread of Life come down from heaven.

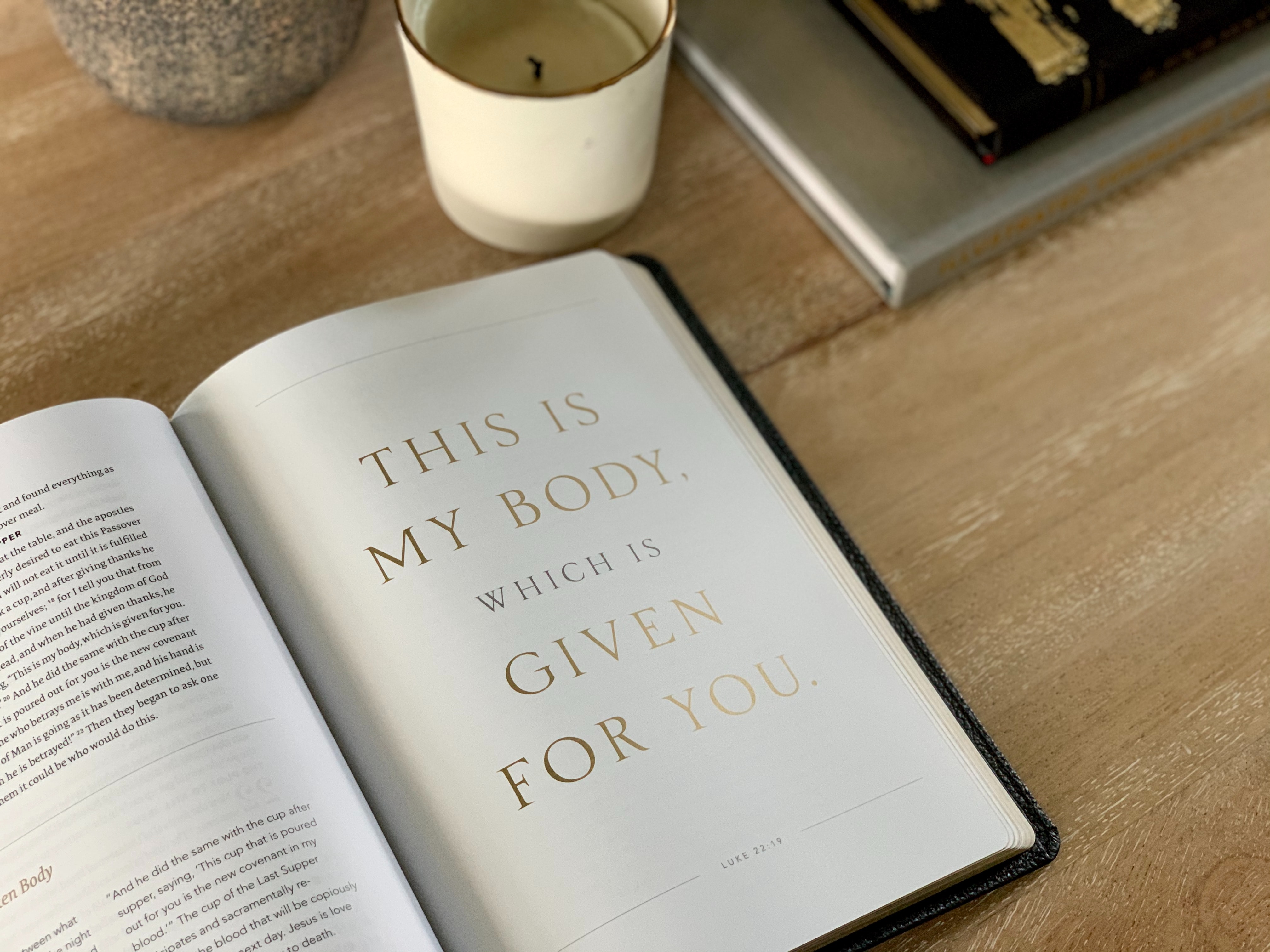

In the reading for the following Sunday, Jesus throws his audience a curveball. Specifically declaring himself to be the Living Bread come down from heaven, Jesus says, “Whoever eats this bread shall live forever; and the bread that I shall give is My flesh for the life of the world.”

The Solemnity of the Assumption supplanted the usual Sunday reading wherein Jesus, quite graphically, tells the crowd that, to gain eternal life, they must eat his flesh and drink his blood. This causes a great deal of consternation.

On the 21st Sunday of Ordinary Time, the Gospel reveals the upshot of this teaching: many of Jesus’ disciples find this “a hard saying” and leave his company.

Aware of its connection, John takes pains to tell his readers that it was near Passover when Jesus taught this in the synagogue at Capharnaum (6:4, 59). Remember, John’s description of the teachings of Jesus appeared at the end of the first century. Internal evidence shows that John had the other three gospels in front of him. To them he adds some events, while elaborating on others already described. One of his goals is to make sure there’s no confusion in doctrine.

It is possible, reading the first three Gospels and 1 Corinthians, to understand Jesus’ words at the Last Supper, “This is My body; this is My blood,” in a symbolic manner. In chapter 6, John removes that possibility. St. John shows that Christ’s teaching was a thunderclap to His first listeners.

Because of the prevalence of their living in the midst of Gentile nations, not to mention the caravans and other forms of commerce, trade and travel surrounding them, Galileans spoke Koine (common) Greek almost as often as they spoke Aramaic. St. John, some 60 years later, writing for Greek readers in Ephesus, makes sure they understand the literalness of Jesus’ statements as much as the Jews who first heard him.

Instead of the Greek word, phagos, a genteel word describing polite dining, Christ shockingly used the word trogos: “munch, chew, gnaw.” Ordinarily, the word described animals ripping apart their prey.

The disciples did not misunderstand the words of Jesus.

The Greek, skleros, so often interpreted into English as “hard saying,” in reality means something far worse. Skleros describes something “disagreeable, offensive, even disgusting.”

You might want to take the time to reread John 6. Try, if you would, to hear Jesus as his opponents first heard him, asking each other in shocked astonishment, “How can this man give us His flesh to eat?” Many of them found this teaching revoltingly vile.

Given the chance to backtrack, Jesus only becomes more graphic. Neither his followers nor his opponents understand Jesus to speak in some airy, nebulous, vague metaphysical way.

Think about these first disciples.

They’ve followed Jesus for a year or two, having heard his stories describing God’s love. They had seen him cure the blind and lame, drive a legion of demons into a herd of swine, and especially, witnessed him create food enough to feed thousands.

Jesus knew the roots of their faith did not go deeply enough to comprehend the spirituality he would later explain. He gave them no symbolic imagery. He gave no explanation. He gave them no out. They didn’t trust him, so he simply gave them leave to go. And some of these followers abandoned him. Their departure unquestionably saddened and dismayed Jesus.

It is one of the most poignant moments of his life. One can feel the sorrow and apprehension as Jesus turns to the Twelve and asks, “Do you also want to leave?”

He’s giving them a chance to avoid heartache and persecution, flogging, beheading, and crucifixion. He gives them the chance to go back to their families, their nets and all the joys of ordinary life.

There is a moment of silence. Then, as he would do again in a few months at Caesarea Philippi, Simon Peter boldly steps forward, putting into words what the others, perhaps, only thought: “Master, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life. We have come to believe and are convinced that You are the Holy One of God.”

This idea has to be first and foremost in our thoughts when walking up the aisle to receive the Body and Blood of Jesus in the Holy Communion: “You are the Holy One of God.” Without it, our communion is earthbound and meaningless.

When attending Mass this Sunday, recall the words of St. Paul in Ephesians 5:2, “Christ loved us and handed Himself over for us as a sacrificial offering to God.” We, therefore, with a loving heart should confess, as did St Thomas, that the Eucharistic Jesus is “My Lord and My God.”

Sean M. Wright, an Emmy-nominated television writer, is a Master Catechist for the Archdiocese of Los Angeles. He is also part of the RCIA team at Our Lady of Perpetual Help parish in Santa Clarita, CA. He responds to comments sent him at Locksley69@aol.com.