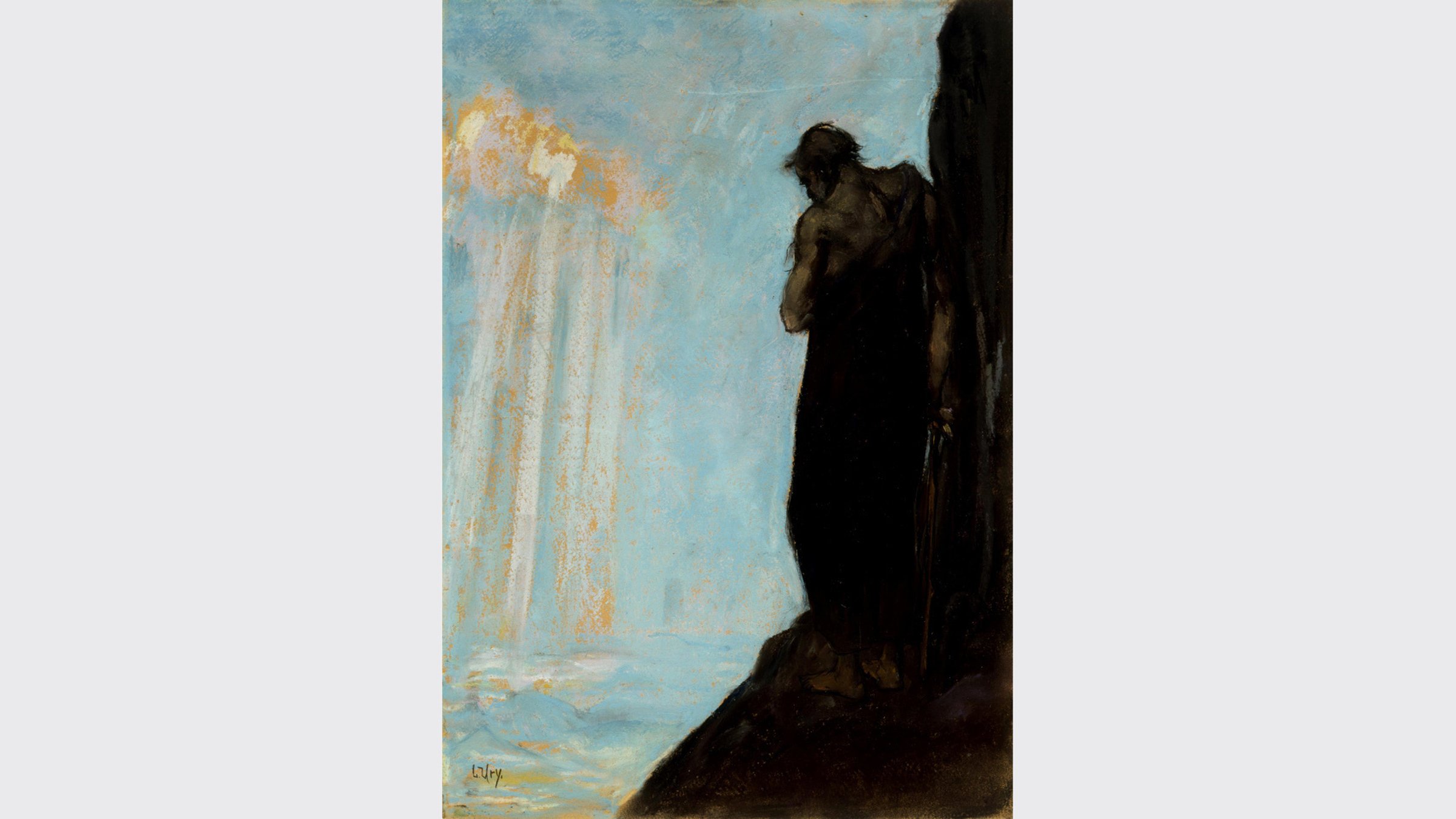

At about this time in the semester, my students study the person of Moses. I love to show them a pastel drawing by German Jewish artist Lesser Ury, Moses Looks upon the Promised Land. The canvas is split cleanly between light on the left and darkness on the right. On the right, Moses, with his back to us, stands balanced upon a narrow ledge, his right side leaning against the rockface of Mt. Nebo. His head is bent, perhaps in sadness, perhaps better to see what lies below. What lies below and beyond him is a bright skyscape, punctuated by a burst of orange and white whose rays travel downward through the azure expanse.

Moses stands alone and in shadow, clad in a ragged garment, his feet, shoulders, and arms bare, a decidedly untriumphant figure. One could interpret this as an unequivocally bitter moment: everything for which Moses has given his life ends here, unfulfilled. Here on Mt. Nebo Moses will die, prohibited from entering the Promised Land because of his failure to manifest God’s holiness to Israel (Deut 32:51), presumably at the infamous event at Meribah in the desert.

And yet, several details make Ury’s drawing in fact a powerful exposition of theological hope, not despair. The bright blue frames Moses’s bent head and occupies more of the canvas than the darkness of Moses’s ledge; in fact, the darkness serves mainly to accentuate the brightness. The ginger and beige notes in sky and land call to mind the “milk and honey” flowing in the Promised Land, and the fact is that, while Moses can only look upon that land, he did succeed in bringing Israel to its threshold. After his death, his spiritual children will indeed enter it. More than that, Moses’s feet are bare: as at the burning bush, he stands in the presence of the All-Holy. Soon what he has always most deeply desired will take place: he will see face to face that God whom he has loved and served. And he knows that, after his death, God will continue to remain faithful to the people He has chosen.

Ury created this work around 1928, when the shadow of Nazism was beginning to fall heavily across his country and his people. And yet, the Jewish people would not even exist in 1928 were it not for God’s constancy throughout the preceding millennia. Their very survival was a living testament to God’s power and care. Ury, who died in 1931 at the age of 70, could trust that darkness would never ultimately overcome the light of God’s truth and fidelity.

On the feast of the Presentation this year, our Sisters heard a homily that brought new, and related, insight to a biblical passage we pray daily, the words of Simeon upon receiving the Christ Child into his arms. Simeon assures God that now he can die in peace, because he has seen “your salvation, which you prepared in sight of all the peoples, a light for revelation to the Gentiles, and glory for your people Israel” (Luke 2:30-32).

How is it that Simeon can manifest such serenity? He will not see the wonders this Child will work, let alone the wonders to be worked through His Church. And yet, that is the point: Simeon does not need to see what will come. To see what has already been given is assurance enough of the goodness of God and His ultimate triumph. “And the light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it” (John 1:5).

Sr. Maria Veritas Marks is a member of the Ann Arbor-based Dominican Sisters of Mary, Mother of the Eucharist.