John, John, bad King John

Shamed the throne that he sat on;

Not a scruple, not a straw,

Cared this monarch for the law;

Promises he daily broke;

None could trust a word he spoke;

So the Barons brought a Deed;

Down to rushy Runnymede.

— Bad King John by Eleanor Farjeon, Friday, June 27, 2014

We last saw John Lackland’s excommunication lifted, welcomed back into full communion with the Catholic Church. This, only after accepting Pope Innocent III’s choice of Cardinal Stephen Langton — whose appointment the king had opposed for eight years — as archbishop of Canterbury and primate of England. Another condition was the royal promise to lead a Crusade to the Holy Land as had his brother, Richard the Lionheart. His deposition now set aside, King John could reclaim his subjects’ allegiance. John took one more step to preserve his kingdom:

"[W]e do offer and freely grant to God, and to His holy apostles Peter and Paul, and to the Holy Roman Church our Mother, and to our lord the Pope Innocent III, and his successors, all the right of patronage which we have in the Anglican chulclhes [sic.] … for the remission of our sins and those of our whole race, both living and dead."

John’s change of mind was hardly due to any change of heart. By this act he made England a fief belonging to the Holy See. Albion’s king remained, but he became the pope’s vassal. Innocent was now England’s overlord.

At the time of John’s excommunication and deposition, Pope Innocent had encouraged Philip Augustus, king of France, to invade England. By the same token, the English barons felt they also could rebel, although Cardinal Langton counseled against it.

Giving in to the pope was merely a political stratagem. Now, to attack John was to attack the Supreme Pontiff. With only soldiers of fortune and other freebooters propping up his throne, John regarded giving in to the pope a master stroke of diplomacy.

This ploy only stalled King Philip’s invasion; his son, Prince Louis, continued to prepare to invade France’s ancient enemy. Neither did it reconcile England’s feudal lords to Lackland. They resented the king’s extortionary scutage payments needed to pay the mercenaries. Richard had levied scutage only three times during his 10-year reign; John did so 11 out of 14 years.

What especially galled the nobles was that their money wasn’t spent to defend England, but for holding on to Plantagenet lands across the channel. So much gold and silver had been stuffed into John’s French castles, actual coin of the realm was difficult to find in England.

Philip Augustus had already wrested Normandy and Anjou from John and was working on taking over the Aquitaine. Due to his continual military ineptitude, England’s king acquired a new nickname, “John Softsword.”

Barons not paying scutage were obliged by oath to leave their families and join the king in some or another military venture, supplying their own horses, arms, armor, transport, food, drink, and pay for their men at arms. Obtaining certain guarantees of feudal rights, therefore, took on even greater urgency for the barons. So their plotting continued.

Recall that, in England, the feudal system was based on an agrarian economy. The kingdom’s wealth began with seed being sown in the spring and crops taken in with the autumn. In every town, shire, county, barony, duchy and earldom, it was a commonplace to see titled nobility labor alongside yeoman farmers, freeholders, peasants and serfs during the harvest. So, when the barons were called to war, every person in the kingdom was the poorer for it.

When John next demanded “service or scutage” in the summer of 1213, many barons rebelled, refusing to provide either. In 1214, so as to diffuse rising tempers, Cardinal Langton called for a Great Council to give the barons a chance to voice their grievances. Envoys of townships would also be included. It was the first representative assembly on record in England.

With civil war looming, England’s bishops met with the barons and delegates gathered at St. Paul’s Cathedral, London. Langton, the former professor of theology, rhetoric and jurisprudence, reminded the gathering of the Charter of Liberties from 1100, part of the coronation oath of Henry I, the conqueror’s son. Langton read aloud the Charter’s 14 clauses among which were promised: “freedom … from taxes or foreclosures” on lands belonging to “the Holy Church of God”; an insistence that heirs were not be deprived of inheritances; women be allowed to marry freely and upon their husband’s death to keep their dowries; “If any of my barons or men commit a crime … he shall make amends according to the extent of the crime.”

Cardinal Langton thus showed existence of legal precedent by which certain of the king’s actions were constrained by law. Upon hearing their rights proclaimed at the Great Council, the barons demanded that John abide by these rights and liberties.

John was in no hurry to comply. On May 17, 1215, however, the barons brought the matter to a head by capturing the Tower of London. Only then did John realize they meant business. With the other English bishops, Cardinal Langton strove mightily to keep the peace and avert civil war. The king and the barons finally agreed to meeting at a Thamesside meadow near London, a greensward called Runnymede.

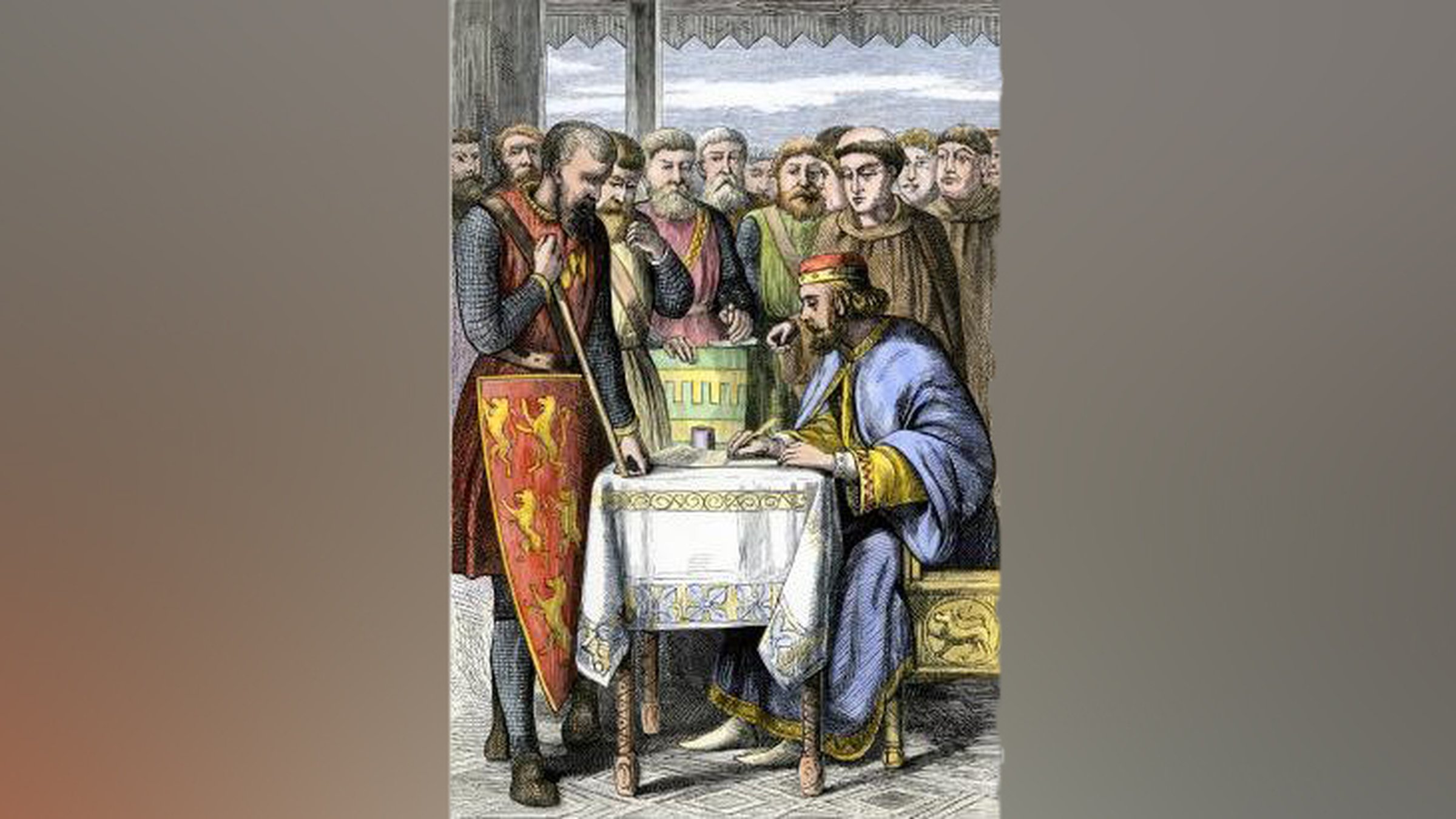

The faceoff between the barons and King John began on June 10. Vibrantly hued pavilions were erected on the lea. Colorful coats of arms distinguished the surcoats of the lords and their king as they met to discuss rights given the Church and the peers of the realm. The results would come to affect every farmer, merchant, landowner, yeoman, villein and serf.

The archbishop presented to the king and his advisors 48 propositions worked out in a document called the Articles of the Barons, based on the Charter of Liberties. Among the laws listed therein, shires were to have their own courts of law so that plaintiffs and defendants need not travel to whatever city where the king was holding forth. Free men were not to be over-assessed for civil penalties, which were to be “in proportion to the nature of the offense.”

A free man was to be allowed trial by “the judgment of his peers.” Of course, the barons insisted, “No scutage or aid is to be imposed in the kingdom except by the common counsel of the kingdom.” Article 30 contained the all-important statement of what should lay behind all systems of justice: “Right is not to be sold or delayed or withheld.”

John parleyed with the barons and bishops for five days while scribes wrote down all items agreed upon. On June 15, the work was, at last, completed.

Illustrations to the contrary, King John did not sign the document with quill pen and ink. Nor, as some movies striving for historical accuracy depict, had he lugged the sealing machinery from a stronghold in London to imprint the Great Seal of England on Magna Carta, the Great Charter of Liberties granted beneath the picturesque oaks of Runnymede.

The barons withdrew, satisfied. Cardinal Langton set off for Canterbury. Magna Carta was prepared within the royal chancery where the Great Seal was affixed as any other document was sealed. Scribes then prepared copies of Magna Carta for dispersal to townships throughout the realm, four of which still exist.

All the while, King John lived up to his deceitful reputation. Dispatching a special messenger to his overlord, John misrepresented the events at Runnymede whining that he, Pope Innocent’s vassal, had been forced to comply with the barons’ demands, instigated by Cardinal Langton, to grant the Charter.

As Maisy Sullivan pointed out, “The dispute between King John and Pope Innocent III over his appointment to Canterbury was a major factor in the crisis that produced the Magna Carta.” It thus is with a note of irony that Innocent, taking John at his word, decreed Magna Carta null.

The pope ordered Cardinal Langton, as primate of England, to publish his order excommunicating the barons involved. They were so notified but, aware of the anger growing among the English during years of interdict, the cardinal thought better of enraging them further by tacking up copies of the pope’s bull of excommunication to the door of Canterbury cathedral and others throughout the kingdom.

Cardinal Langton was already in Dover on his way to Rome to attend the Fourth Lateran Council when a royal messenger caught up with him. Gleefully, King John had forwarded Pope Innocent’s decree suspending Langton from exercising power as archbishop of Canterbury and recalling him to Rome to explain his actions.

Well, the cardinal was already on his way to Rome. Only now he felt dubious about the reception he would receive upon arrival.

Sean M. Wright, MA, an Emmy-nominated television writer, is a Master Catechist for the Archdiocese of Los Angeles. He is also part of the RCIA team at Our Lady of Perpetual Help parish in Santa Clarita, CA. He responds to comments sent him at Locksley69@aol.com.