“Santa Clarita!” Mom cried out in alarm. “That’s the end of the world. I’ll never see my grandson again!”

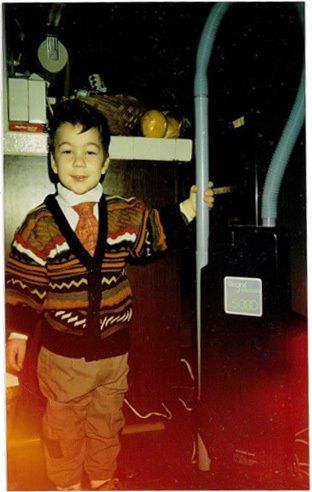

December 24, 1996, found me and DeForeest, my 7-year-old son, speeding down the 101 — the Hollywood Freeway. The Christmas tree of lights atop the Capitol Records building told the boy we were once again in Hollywood. Eleven months before, we’d given up an apartment there for a condo in Santa Clarita. Tonight, we were expected at the family manse on Romaine Street where I grew up, which my mother, Valentina, still called home. Frequent visits convinced her that Santa Clarita was not light years away.

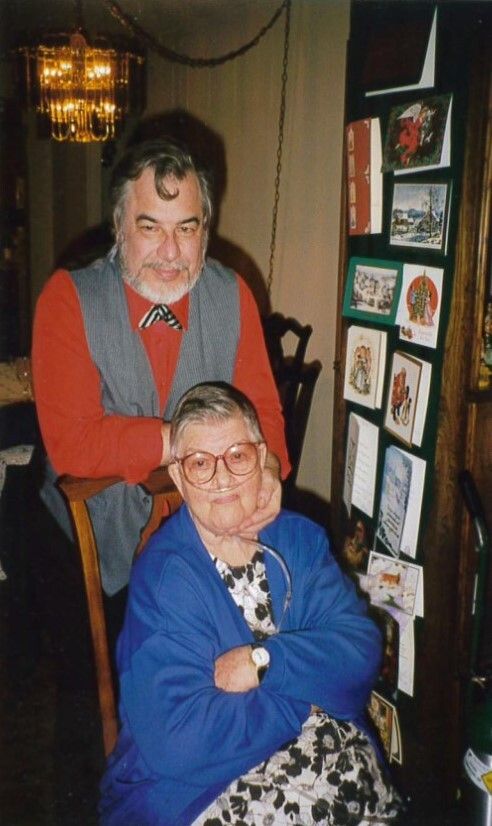

Mom was a little ball of a woman. She was then 75 — graying, rheumatic, arthritic, asthmatic — she missed driving to Mass, relying now on extraordinary ministers of Communion from Christ the King, her parish since 1945, to bring her the Holy Eucharist. Understaffed, their visits were infrequent.

She and DeForeest were always very close, especially after Papa died in 1993. For several months, despite being shackled to an oxygen tank, Mom drove the boy home from kindergarten to look after him until my wife, Kelly, or I picked him up.

I felt guilty about the setup only briefly. Mom and DeForeest simply adored each other.

He often insisted that she bring him home by way of the Hollywood Memorial Park Cemetery on Santa Monica Boulevard. He never tired of Mom pointing out Douglas Fairbanks’ reflecting pool, D. W. Griffith’s obelisk, Cecil B. DeMille’s cenotaph, Tyrone Power’s marble bench, and Mel Blanc’s headstone reading, “Th’, th’, th’, that’s all folks!” He was fascinated by her stories about movie stars from the 1920s through ‘90s and loved the attention. DeForeest is now 31, COVID-19 causing a pause in his college nursing courses, but he could still conduct a tour of the place singlehanded, despite the cemetery being renamed Hollywood Forever.

Once home, Mom let DeForeest have fun — like pretending he was a scientist. Sitting on a stool at the kitchen sink, swathed in a large apron “lab coat,” he made “concoctions” as Mom laughingly described his “experiments” — such as scrambling eggs with milk, salt, pepper — and blue, green or red food coloring. DeForeest, the only grandson, got away with things around the family homestead my sister, two brothers and I would have been skinned for.

This particular Christmas Eve my sister, Helen, had a severe cold. David, her doctor-husband, not taking a chance with Mom’s asthma, thought it best to stay home. Older brother, Ben, and his wife, Sharon, were visiting her parents up north. My younger brother, Bill, was playing a hot saxophone aboard a Caribbean cruise ship — so DeForeest and I were the party.

Over turkey, Mom and I swapped stories about Christmases past, such as when Papa’s choir came for hor d’oeuvres and creamy Alexanders between the 8.30 and noon Masses, and how she saved money by making me a Davy Crockett cap from an old mink collar.

DeForeest’s merriment was a tonic for us both, but Mom began wheezing so we hooked her up to the concentrator and cleaned up. Sitting in her motorized armchair, Mom resumed crocheting to carols sung on TV. She and Papa always had their hands busy while in repose, crocheting or quietly praying the rosary.

The move caused Mom’s neck to ache, so DeForeest gave her a massage. Even then he knew instinctively what muscles to knead until his healing touch brought her relief. Her grandson’s ministrations notwithstanding, Mom let us know she was unable to muster strength enough to join us, annoyed that her disabilities were getting between her and receiving Holy Communion at midnight Mass. Still, she declared, she wasn’t sleepy. We were welcome to return for kolaches, the delicious Czech pastries she and Papa made each Christmas.

DeForeest and I drove off to our former parish, Our Mother of Good Counsel. Inwardly I was kicking myself. I’d been a Eucharistic minister there; I should have carried my pyx to bring the Holy Eucharist to Mom. I never thought she’d be unable to join us.

During Mass an idea struck.

Ducking into the sacristy afterward, Fr. Michael McFadden, the pastor, was removing his vestments. I described my dilemma, wondering if I could borrow a spare pyx. Fr. Mike answered by reaching into a drawer to retrieve a corporal, the square, white linen cloth on which the chalice and Sacred Host rest at Mass. He unfolded it on the counter. Still clad in his alb, he dashed off to the tabernacle, returning with a Host, which he placed in the center square made by the cloth’s stiff folds. As he folded it up I regarded the little package dubiously.

“Isn’t there a chance the Host might slip out?”

Fr. Mike chuckled, “No. I’ve had a lot of experience doing this.”

He handed me the starched linen square with its precious Cargo. “Be sure to wish your mom a Merry Christmas for me,” he smiled.

The car presented another problem. How to drive and keep the Holy Eucharist safe? None of my pockets were wide enough to hold the corporal. If I folded it again I might crush the Host within. Dashboard? Too easy to slip off. I turned to my son.

“DeForeest, tonight you are Christopher.”

His face became a question mark.

I related a condensed version of the story about the strong, gigantic man who carried the Christ Child on his shoulder across a raging river. Jesus told the giant that, henceforth his name would be “Christopher.”

“Christopher means ‘Christ-bearer,’ so while I drive you need to carry the Baby Jesus in this cloth.”

Seatbelted, the corporal resting on his knees grasped tightly with both hands, DeForeest gazed at it with reverent intensity. “Don’t worry, Papa,” he said softly. Then, his eyes twinkling, he flashed me a sudden conspiratorial smile. “Grandma will sure be surprised to see the Baby Jesus!”

Back on Romaine Street the soft light behind the curtains of Mom’s bay window shone through the chill, crisp air. DeForeest handed me the corporal. We strolled up the walk to Mom’s door, which I unlocked. DeForeest bounded in.

“Grandma!” he called out excitedly, running to hug her. “We have a special Christmas Visitor for you!”

Still sitting, Mom looked at him, uncomprehending. As if on cue DeForeest stepped back, gesturing toward me. Unfolding the corporal I held the Blessed Sacrament before her.

Surprise, joy and love shone in my mother’s eyes. Dropping her crocheting onto her lap, she raised her right hand to her breast and bowed profoundly to the Eucharistic Jesus. She began sobbing. Hot tears streamed down her round, creased, careworn cheeks before she could raise her eyes again.

“I thought I was going to miss receiving Holy Communion tonight,” she said, smiling through her tears, “but you’re right, DeForeest. You and your father brought me a very special Christmas Visitor.”

I’ve lived many years among books on Catholic history and theology. Achieving a summa cum laude with my degrees, I came to think I knew a lot about the faith.

My mother, on the other hand, born in 1921 in Elyria, a tiny hamlet in the wilds of the central Nebraska hinterland, saw a priest once a month when he came to celebrate Mass. Mom’s six weeks of catechism at the age of 7 was her only formal training in Catholic teaching.

Looking into my mother’s radiant face as she gazed so rapturously at the Word made flesh that early Christmas morning, I know I witnessed a special miracle of love, the memory of which has provided a lesson in humility every day since.

Wondering how to help out around your parish? Why not check to find out when the next extraordinary minister of Communion course is scheduled and sign up? Then you, too, can become “Christopher,” carrying the Christ Child to the elderly and disabled who might otherwise have to wait long stretches into the New Year for their Merry Christmas.

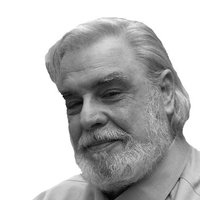

Sean M. Wright, MA, an Emmy-nominated television writer, is a Master Catechist for the Archdiocese of Los Angeles and is on the RCIA team at Our Lady of Perpetual Help in Santa Clarita, Calif. He responds to comments sent him at [email protected].