Sean M. Wright interviews Turner Classic Movies' "Czar of Noir" Eddie Muller about his new book, Dark City, and how the genre of film noir may — or may not — intersect with Catholic thought.

They’re all here: Dan Duryea, Edmond O’Brien, Robert Ryan, Dennis O’Keefe, Richard Widmark, Robert Mitchum, John Garfield, Dana Andrews, Humphrey Bogart, Fred MacMurray, Lawrence Tierney, Edward G. Robinson, Barbara Stanwyck, Ida Lupino, Audrey Totter, Betty Davis, Lana Turner, Gloria Graham, Joan Bennett, even pinup girls Betty Grable, Rita Hayworth, Marilyn Monroe. All the actors and actresses whose characterizations made film noir come to sleazy, steamy, despairing, disreputable life as denizens of the Dark City.

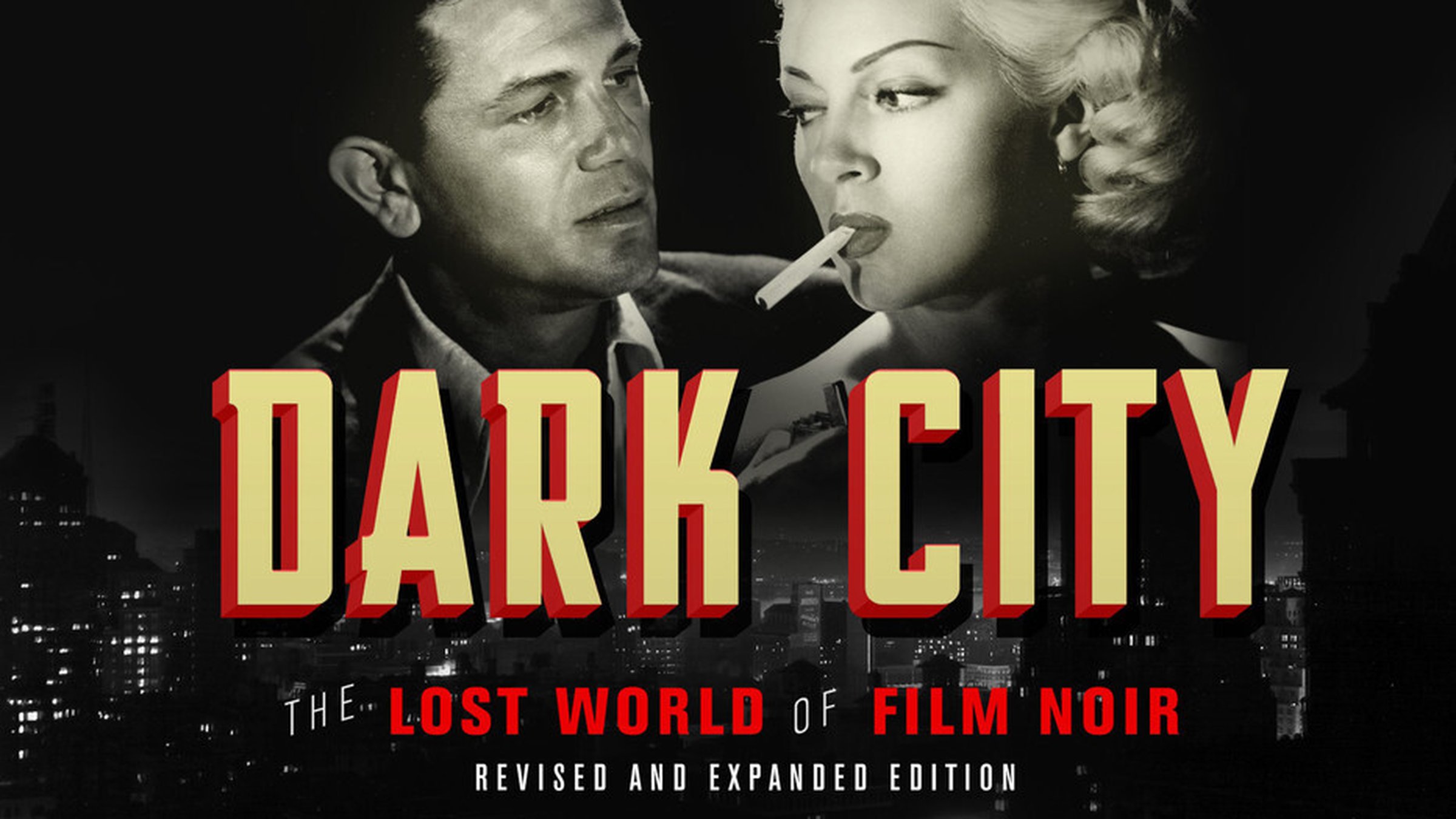

This filmic art form is embraced by Eddie Muller, the genre’s most visible expert, who’s come out with an expanded edition of a superbly written book, Dark City (Running Press, 2021), a veritable seminar explaining cinema’s disreputable stepchild.

With a wry writer’s conceit, Muller has named his chapters, for the shady zones of the Dark City—Blind Alley, Shamus Flats, Vixenville, Thieves’ Highway, The Stage Door, The City Desk and so on. He then explains which films are found in these environs of the Dark City.

I confess to watching those old, black and white B movies usually late at night, without much curiosity, if nothing else was on. Every so often something caught my interest, like Laura, with its inventive quandaries and psychological twists; or DOA’s intriguing premise of a man being poisoned, having no idea why.

Then I caught “Noir Alley” on Turner Classic Movie network, started paying attention, and began to change my mind. “Noir Alley,” airs Saturday nights, repeated on Sunday mornings, is hosted by Eddie Muller, the self-styled “Czar of Noir”.

Within the following interview, readers will become aware that Eddie, who possesses a Catholic background, acknowledges that theological strains and biblical themes exist in noir. At the same time, he resists dwelling on them. The same thing is true in Dark City.

While I had hoped that Eddie would describe some Catholic-themed films such as I Confess, Edge of Doom, The Wrong Man and Boomerang in Catholic terms, he chose to see them as examples of a despairing worldview current in the period following two world wars and the Great Depression. More following this first segment.

# # #

Sean M. Wright: Eddie, first off, allow me to compliment you on assembling a massive amount of information presented in an entertaining, well written, and attractive format. Naming chapters after various byways and regions in the Dark City was a stroke of inspiration.

Eddie Muller: Thanks very much, Sean. I appreciate your saying that. I’m very pleased with the deluxe treatment Running Press gave the book.

SMW: Getting down to business, Elia Kazan’s Oscar winner Boomerang (1947), and Mark Robson's Edge of Doom (1950) both detail the murder of priests, a shocking, almost unheard of, concept to people in the US of the 1940s and '50s. Yet you don’t spend much time on these two movies. Any second thoughts?

EM: I have second thoughts all the time about stuff I didn’t include, but you can’t fit in everything. I bypassed Boomerang because it’s more of a courtroom drama than a true noir. Discussing theological aspects of film noir, I see them as part of an organic artistic movement, I can’t know the actual intentions and motivations of the writers, directors and producers.

SMW: But isn’t there often a theological basis behind film noir storylines?

EM: I find it dangerous and misleading to declare “film noir represented this, or film noir represented that.” Given that, I will say that if there’s an overriding theological interpretation one could ascribe to the noir movement, it would be that the films, taken as a whole, are suggesting for the first time in popular entertainment that we may exist in a godless world.

SMW: Would you say that noir at its best emphasizes the struggle between light and darkness?

EM: Well, I don’t believe there is a single movie that directly expresses that idea. Rather, it’s the

cumulative effect of so many similar films made and released at the same time, the “movement”. Were I to sum up the overriding attitude of noir in one line of dialogue (my own), I’d say, “Prayers aren’t gonna be answered, Try another plan.” In noir that other plan usually isn’t legal.

SMW: Did the rise of dictators in the 1930s and the necessity of destroying their evil by force of arms create an air of disillusionment replacing the certainty of the basic goodness in mankind so popular in America cinema up that time?

EM: Hey, we’d been through WWI, “The War to End All Wars”. That gave rise to the first wave of pessimistic “hard-boiled” American fiction out of which ’20s and ’30s “pulp fiction” grew. The one-two punch of the Depression and WWII showed the devastating effect of man’s rapacious greed and evil. The cost of countering it, and conquering it, was paid in human lives. No miracles involved.

SMW: And the disillusionment?

EM: I suspect it had a profound effect, especially on writers. However, I think all these calamities bred distrust in Man, not God. The political writers told stories about the ease with which the capitalist system could be corrupted—a big theme in noir—and they were blacklisted for it.

SMW: So, you see noir as a reaction against reactionary politics?

EM: The writers’ issue wasn’t with God; it was with their fellow man. Writers and producers

also bristled against the largely Irish Catholic Production Code Office, which operated as an arm

of the Catholic Legion of Decency.

SMW: You don’t see the good intentions of the Production Code and Legion of Decency?

EM: Well, essentially both systems saw no difference between God’s Law and man’s law. Writers and artists, who are natural contrarians, often simply wanted to tell stories.

SMW: Sometimes scandalous stories, according to the lights of US culture at the time.

EM: They were an alternative to the eternal optimism required of Hollywood product during

those tumultuous years of Depression and war.

SMW: We almost spoke about Edge of Doom and its tale of a priest being killed not getting a lot of space in Dark City,

EM: It was a tough call on Edge of Doom. Partly this is because I have conflicted feelings about the movie, knowing its tumultuous production history.

The film as it was originally made by director Mark Robson, and shot by Harry Stradling, was a pitch-black film noir, possibly superior in that regard to the more famous Naked City, which was also shot on location in New York. But while the film was in post-production producer Samuel Goldwyn feared it was too bleak for audiences and he got cold feet.

Goldwyn ordered reshoots, inserting two new characters—Father Roth (Dana Andrews) and Joan Evans as Farley Granger’s love interest—neither in the original draft. Both Granger and Evans told me that they detested shooting the film and were exasperated by the constant rewrites, done mainly because Goldwyn (and the distributing studio, RKO) was afraid of condemnation by the Church.

Farley literally tried to run out of a screening I’d invited him to when he learned that novelist Leo Brady’s family was in the audience. So, I found it hard to write about this film without mentioning all this backstory, which, I felt, was an unnecessary detour. There are parts of the film that are brilliant, but I find it very uneven.

SMW: Getting back to theology, can it be said that film noir emphasizes sharp encounters between good and evil, God and Satan, while cinematically describing rather confusing, murky and otherwise tawdry aspects of ordinary lives? Isn’t noir marked by moody pessimism, a cynical conviction of the futility of life, and a despairing rejection of Divine Providence?

EM: I think that’s overstating it. The stories don’t reflect the futility of “life,” but the futility of humans who succumb to material or sexual desires at the expense of morals, ethics, and common decency. Far from a refutation of Christian principles, these stories are like a catechism. I’ve many times described the essential noir plot as a “tale of karma.”

SMW: Karma is not a Christian belief.

EM: Well, it’s largely the same thing as reaping what you sow [Galatians 6:7].

# # #

Eddie Muller describes the despairing theology of film noir as, “Prayers aren’t gonna be answered, Try another plan.” In noir that other plan usually isn’t legal.”

In Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, Cassius comments, “The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves.” Taking a tack from this remark, Eddie explains how it is evident, following civil strife, world war and widespread financial depression that film noir is constructed to show how “all these calamities bred distrust in Man, not God.”

At the same time, Eddie is not at all sure that the Production Code and the Legion of Decency were Good Things. He thinks they raised too many artistic road-blocks. This may be an overgeneralization. Any number of movies are better for their creative dialogue and restraint in portraying sin and vice. A cry in the dark is often more terrifying than blatant displays of blood and gore; a lifted brow can be more seductive than exposed and writhing bodies.

Many states and municipalities had their own, often more stringent, regulation boards on what constituted “decency” than was outlined by the Legion. A book or movie tagged “Banned in Boston” was practically assured a successful run in the rest of the nation.

[Part 2 of Eddie Muller’s interview will appear in the next installment of Detroit Catholic.].

Sean M. Wright, MA, an Emmy-nominated TV writer, is a Master Catechist for the archdiocese of Los Angeles and a member of the RCIA team at his parish, Our Lady of Perpetual Help in Santa Clarita, Calif. He responds to comments sent him at Locksley69@aol.com.