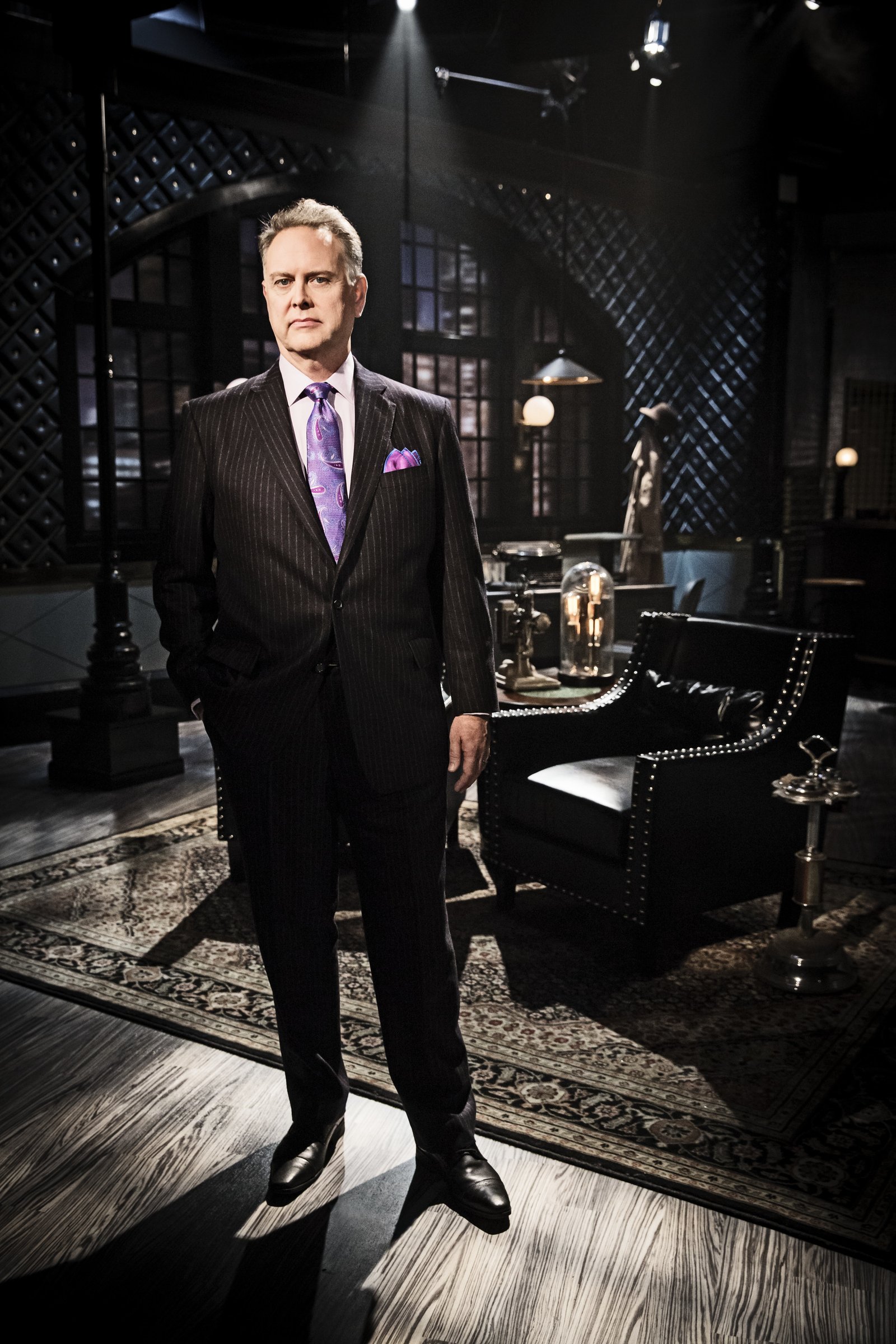

Sean M. Wright interviews Turner Classic Movies' "Czar of Noir" Eddie Muller about his new book, Dark City, and how the genre of film noir may — or may not — intersect with Catholic thought.

Film noir — gritty melodramas intent on highlighting dark, sometime seedy lives, habitually American: men and women who missed grabbing the ring on the merry-go-round. The roles are enhanced by stark or shadowy black-and-white cinematography, experimental camera angles and often offbeat direction.

As founder and president of the Film Noir Foundation and co-programmer of the San Francisco Noir City Film Festival, Eddie Muller has been instrumental in restoring many films from disintegration or saving them from flat-out destruction. He has made it his lifework to spark greater public awareness and appreciation of the noir art form.

Eddie’s new book, Dark City (Running Press, 2021) makes no demands to read the book in sequence. Each chapter is complete in itself. Eddie has the good grace to allow his readers the freedom to pick up his heavy tome (260 pages) and start a quick study in any of the Dark City’s provocative regions. As for instance:

It’s the little guys who always take it in the shorts — bank tellers, teachers, truckers, letter carriers. The juiceless citizens of Dark City. They don’t know anybody who can grease the skids or bail them out. Consider Quicksand (UA, 1950), which could have been called Andy Hardy Goes to Hell. It starred America’s rapidly maturing Boy Next Door, Mickey Rooney.

Eddie condenses Rooney’s filmic misadventures as he sinks from one crime to another. The reader comes to realize the film’s title more than describes the downward spiral of wretched events Rooney finds himself caught up in. Eddie’s summation: “Quicksand is the archetypal Blind Alley thriller revolving around the pursuit of money and its pitfalls,” whets the readers’ desire to see if the film is on his streaming service, or scheduled to be broadcast on TCM.

Now back to the interview, opening with a discussion of Divine Providence:

# # #

SMW: Picking up the theme of pessimism following both world wars, is the element of God’s redemption missing in film noir?

EM: I don’t think any of the noir films, individually, reject the notion of Divine Providence. Take one of my favorite movies, Nightmare Alley.

SMW: A complete departure from Tyrone Power’s previously heroic image.

EM: Right. Playing an ambitious “mentalist,” Stan Carlisle, he gets rich with his “all-seeing” con man act. His wife [Colleen Gray], who’s part of the act, rejects him when he starts “sounding all holy” and “acting like you’re God.” It’s a cautionary tale about how easily charlatans can adopt the trappings of divinity to dupe gullible people.

In the end, some people will think a divine hand orchestrates Stan’s demise. But it was definitely Daryl Zanuck who orchestrated Stan’s redemption at the end of movie. He didn’t want audiences to see Tyrone Power reduced to biting the heads off live chickens, which is how the story was supposed to end.

SMW: So … Zanuck provided Tyrone Power’s redemption, not God.

EM: (Laughing), In a way.

SMW: Do you believe that film noir is restricted to America, to more-or-less rundown urban areas?

EM: What do you mean by “restricted”?

SMW: I mean, is film noir only found in movies set in the postwar era, set in rather seedy areas, notably those in the vicinity of downtown Los Angeles, since so many noir films were made at that time in nearby Hollywood?

In my opinion director Anthony Mann’s The Black Book (aka Reign of Terror, 1949) is an example of noir’s sense of menace and political corruption but in a different historical setting, namely the French Revolution.

I think the same is true of Samuel Fuller’s Baron of Arizona (1950), based on the very real attempt by James Reaves [Vincent Price] to make most of the state appear to be a Spanish land grant. Do you know these films? If so, do you agree that elements of noir can be found in them or other film genres?

EM: I love Reign of Terror. It’s essentially the French Revolution as a gangster film, with an undercover man in the middle. And with [cameraman] John Alton shooting it, the noir vibe is thick.

Because I think of film noir as an artistic movement, of course I believe its style and tone seeped over into other genres at the time, especially westerns, like Pursued, Blood on the Moon, Ramrod, Station West, and a few others. Anthony Mann’s 1950s westerns don’t look like noir but they take many of noir’s themes and transpose them to the frontier, like Winchester 73, The Naked Spur, and Man of the West.

Last April I showed a slapstick comedy on TCM, The Good Humor Man, that has noir DNA in it. As does something like Preston Sturges’ black comedy Unfaithfully Yours.

SMW: What specific example of noir — if any — would you present as showing a recognizable sense of reformation or the Christian concept of salvation?

EM: There are two that immediately come to mind, one a botched misfire and one a masterpiece. We spoke of Edge of Doom earlier. It is a 1949 film noir based on a popular book by noted Catholic writer Leo Brady. He was devoutly religious but wasn’t afraid to write stories directly challenging the Church.

In this one, an impoverished young man in Manhattan (played by Farley Granger) kills the local parish priest when he refuses a lavish funeral for the boy’s mother—who never missed a Sunday offertory even though she couldn’t buy food. The kid’s already unstable because the priest refused to bury his father, who committed suicide. It turns into a manhunt for this lost and terrified kid, a descent into a man-made hell.

The movie was so bleak the studio demanded new scenes be shot that provided some hope of redemption. Dana Andrews was brought in to play a good priest, a character who wasn’t even in the original script. The kid’s redemption at the end feels forced and utterly false.

SMW: Okay, that’s one.

EM: Then there’s 1948’s Moonrise, the last great film by director Frank Borzage. Dane Clark plays a young guy wracked by guilt because his father was a hanged for murder. He’s afraid he has “tainted blood.” He’s ostracized, beginning in childhood.

When he kills a long-time tormentor in a fight, he hides the body and tries to live with his inner torment—while he falls in love with his victim’s girlfriend. In the end he “sees the light” and turns himself in, hoping that he’ll be redeemed and get a second chance at love and a normal life.

Normally, endings like this in noir fall flat because they’re enforced, not organic. But Borzge truly believed in the power of love and redemption; it comes through in all his films, even ones as dark as Moonrise. So, yes, there is at least one film noir where the fallen hero is “saved”, as luck—or Divine Providence?— would have it. The film’s a masterpiece.

SMW: Many thanks for taking the time for this interview, Eddie, and good luck with a truly informative book.

EM: Thank you, Sean. I really appreciate your take on the book, and the intriguing and insightful questions.

# # #

Eddie Muller’s thoughts on Farley Granger’s eventual redemption at the end of Edge of Doom is a reviewer’s comment on the film’s content, after speaking to participants. The original story lacked the “happy ending.” He wasn’t rejecting the possibility of Divine Providence.

Eddie’s remarks would be in much the same vein if the movie, To Kill a Mockingbird, showed Bob Ewell, the racist who tries to kill Jem and Scout, realizing how wrong he’s been, shares Sunday dinner with them and Atticus, then marries, Calpurnia, the family’s black housekeeper.

Let me share one last reminder that Running Press has happily spared no expense on turning out a very handsome, beautifully laid out work. Dark City’s lavish illustrations also educate, often showing a story’s birth in a pulp magazine, with classically lurid covers, maturing into typically sordid theater cards and movie stills. It is a book to be savored more than once.

Sean M. Wright, MA, an Emmy-nominated TV writer, is a Master Catechist for the archdiocese of Los Angeles and a member of the RCIA team at Our Lady of Perpetual Help parish in Santa Clarita, CA. He responds to comments sent him at [email protected].