Deacon Steven Morello appointed in July 2023 as archdiocese's missionary to the American Indians, reimagining ministry

DETROIT — While Deacon Steven Morello has been a Catholic and an American Indian all his life, during his upbringing, he was only aware of one of those things.

He knows he’s not the only one.

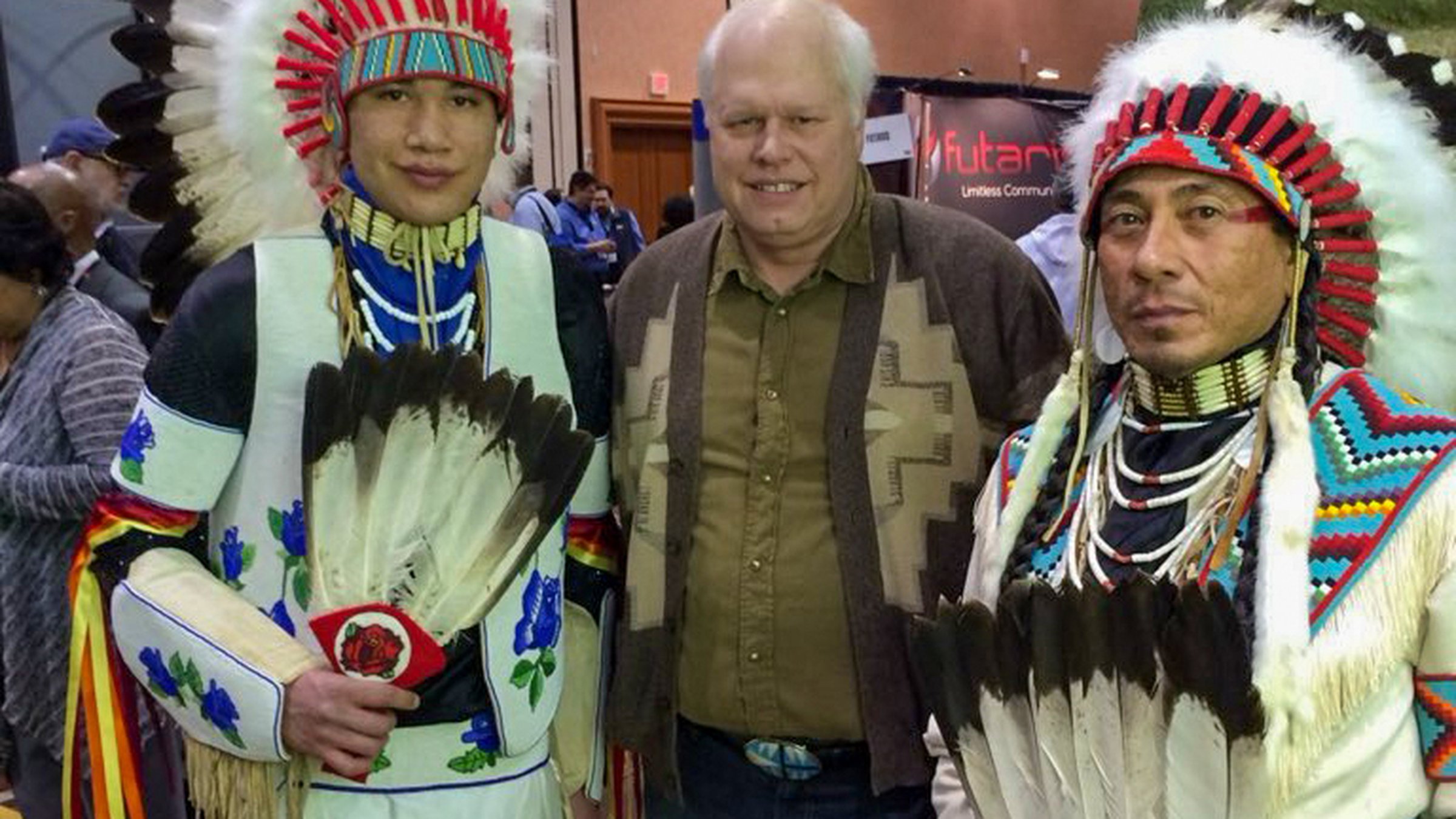

In July 2023, Archbishop Allen H. Vigneron appointed Deacon Morello as the Archdiocese of Detroit’s missionary to the American Indians, a position formerly known as coordinator of Native American Ministry, which falls under the umbrella of the archdiocese’s Office of Cultural Ministries.

Don't miss another story

Did you know you can get Detroit Catholic's latest daily or weekly articles delivered to your inbox? It's easy and free to sign up.

For Deacon Morello, who belongs to the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, the change in terminology is representative of the diverse identities of the American Indian people.

But the title “missionary” also represents the challenge Deacon Morello faces as he seeks out American Indians in southeast Michigan not only to teach them about their Catholic faith, but to help them to better understand their American Indian identity, culture and spirituality.

The Archdiocese of Detroit has had an active ministry for American Indians since the early 1990s, Deacon Morello explained. Based in Dearborn, the St. Kateri Tekakwitha Nicholas Black Elk Circle holds monthly circles and cultural events, led by Fr. Charles Morris, who has volunteered his time for decades.

A deacon for 33 years, Deacon Morello spent years ministering to American Indians not only in his own tribe as the general counsel and chief ethics officer, where he became familiar with American Indian law, but across the country. For two years, Deacon Morello served as director of the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Indian Energy Policy and Programs in the administration of President George W. Bush.

While Deacon Morello fully embraces his heritage, he hasn’t always known that he was American Indian.

“I didn’t become aware of the fact that I was Native American until I was 23,” said Deacon Morello, who also serves at St. John XXIII Parish in Redford.

His revelation came in the mid-1970s, when the federal government ended policies that had systematically destroyed tribes and Americanized Native peoples, beginning with the massacre of American Indians and ejection from their land.

By the early 20th century, the policy had shifted.

“The policy was to make us all white by taking children off the reservation and putting them in the white man schools, forcing them to do white men things and punishing them viciously if they did Indian things,” Deacon Morello said. “After a number of years of being in the schools, they were free to go, but they had no place to go because the reservations didn’t want them anymore; they were white as far as the Native people were concerned.”

With no place to go, these American Indians began to marry outside of their tribes and societies, and began blending in with white society. As generations passed, many began to forget their Native heritage.

From the mid-1940s to the mid-60s, the U.S. government on both the state and federal level implemented a series of laws that ultimately ended the federally recognized sovereignty of American Indian tribes, thus disbanding them and further separating many American Indians from their cultural roots and Native identity. Those policies weren’t overturned until the 1970s, when Native people were given the opportunity to re-establish their tribes and prove their Native heritage.

Deacon Morello’s aunt on his mother’s side provided the necessary proof that the family was American Indian, and Deacon Morello along with his siblings enrolled in their tribe at the encouragement of their mother.

Now, Deacon Morello’s three children and four grandchildren are enrolled as well.

“My grandfather was 100 percent pure-blooded Native American, but his generation were the ones that were sent to the schools; they came out with such a negative impression of Indians that they denied that they were Indian,” Deacon Morello said. “This has come full circle because at one point it was a great pride to be a Native American person, and then it was a great shame, and now once again it is a great pride.”

In his new role with the archdiocese, Deacon Morello has taken over leading the St. Kateri Tekakwitha Nicholas Black Elk Circle, beginning meetings in prayer, followed by a teaching about different elements of American Indian culture.

Then, the group takes time to listen.

“In the American Indian way of doing things, decisions are always made in a circle so that no one is more important than the next. If you go into a board meeting with the long table and someone is sitting at the head, you know right away who the boss is, but in American Indian circles, you can look at that circle all day long and you don't know who the boss is, because everyone's opinion is valued in an equal way,” Deacon Morello explained.

“We have a listening session; I turn the program over to the circle and each one is given an opportunity to speak … because we all have an obligation to listen to each other,” he said.

About a dozen members currently attend these meetings, but Deacon Morello hopes to find more members by identifying Catholics of American Indian heritage in southeast Michigan.

His first goal, however, is to develop the spirituality of the group in a way that is consistent with Catholic teaching and, when possible, the Native understanding of spirituality.

“There are people in the archdiocese who really are Native American and really should be participating in their heritage,” Deacon Morello said. “This is what the multicultural office is all about — we have Black Catholics, we have Hispanic Catholics, and we have Indigenous Catholics, and in each one of those groups there are certain needs in order to help them fully participate in the life of the Church. My mission is to identify those who have Native heritage and help them identify in the life of the Church from their own cultural perspective.”

Recognizing the unique cultures of each tribe, there are different ways to minister to Native people, Deacon Morello explained.

“If I were on a reservation, there would be no question of the Native identity; they understand their identity, their culture and their spirituality perfectly, so the challenge in that environment is for the ministers to figure out how to minister Catholic principles, spirituality and prayer in an environment that is steeped in Native culture, tradition and spirituality,” he said. “I am on the other end of the spectrum, so my challenge is to bring Catholic spirituality to a group of Native people once I identify them and at the same time help those Native people understand their Native spirituality.”

In southeast Michigan, there are no reservations, so Deacon Morello’s main focus is urban Indians, that is, American Indians who are disconnected from their tribes, many of whom aren’t familiar with their culture or history.

Deacon Morello wants to help people trace their ancestry and enroll in their tribes, and would like to establish quarterly circle meetings to bring in tribe leaders to talk to the circle.

He also plans to spread the word through local priests and parishes who might know of American Indians in their parishes, as well as tribes whose Catholic members might be located in southeast Michigan.

Deacon Morello’s office receives funding from the U.S. bishops’ Black and Indian Mission Office, which is led by Fr. Maurice Henry Sands, a priest of the Archdiocese of Detroit. Along with expanding the St. Kateri Tekakwitha Nicholas Black Elk Circle, Deacon Morello also has his eyes set on a loftier goal: the creation of a center of American Indian culture in the archdiocese.

“I would like to set up an American Indian cultural museum or center where we can have different things, different teachings, different displays and Native artisans can come on a regular basis and sell their craft,” Deacon Morello said. “I would like to have a place of our own.”

Find out more

Deacon Morello invites all American Indian Catholics, those who are seeking answers about their ancestry, and friends of American Indians to contact him at morello.steve@aod.org.

Copy Permalink

Native American ministry