In the morning hours of June 11, 1805, dozens of local Catholic families tied up their canoes along the banks of the Detroit River and headed to Ste. Anne’s parish for a “spiritual retreat.” Leading the religious mission was the parish's tireless pastor, Fr. Gabriel Richard, assisted by his associate pastor, Fr. John Dilhet. Together, the two priests had done much for their growing parish, spearheading the formation of two elementary schools, a young ladies’ academy, and even a new seminary for priests. The Catholic community was thriving in Detroit.

Just after the spiritual retreat began, a fire suddenly erupted in the 104-year-old city filled with wooden structures.

"I was occupied," wrote Fr. Dilhet, "with Father Richard when a messenger came to inform me that three houses had been consumed and there was no hope of saving the rest. I exhorted the faithful who were present to help each other, and immediately commenced the celebration of a Low Mass, after which we had barely time to remove the vestments and furniture of the church.”

In just three hours, the entire city was consumed by the fast-moving inferno. The priests could only watch on as the fire destroyed the schools, seminary and Ste. Anne’s historic church. According to the associate pastor, all that was left were the “chimney tops stretching like pyramids into the air.” “It was the most majestic, and at the same time the most frightful spectacle I ever witnessed,” Fr. Dilhet said.

The devastation and suffering left in the fire’s wake spurred Ste. Anne’s pastor to help those in need. “Day and night” Fr. Richard sought to assist all who were left homeless “without regard to creed or race.” The French priest negotiated with American military officials to secure tents and other provisions for the needy. Fr. Richard was able to obtain emergency foodstuffs from farmers throughout the Detroit River region. He quickly set up a new parish center just south of Detroit and began to speak positively of the future of the city. The city of Detroit’s enduring motto, Speramus meliora; resurget cineribus — “We hope for better things; it shall arise from the ashes” — was coined by Fr. Richard in the aftermath of the fire.

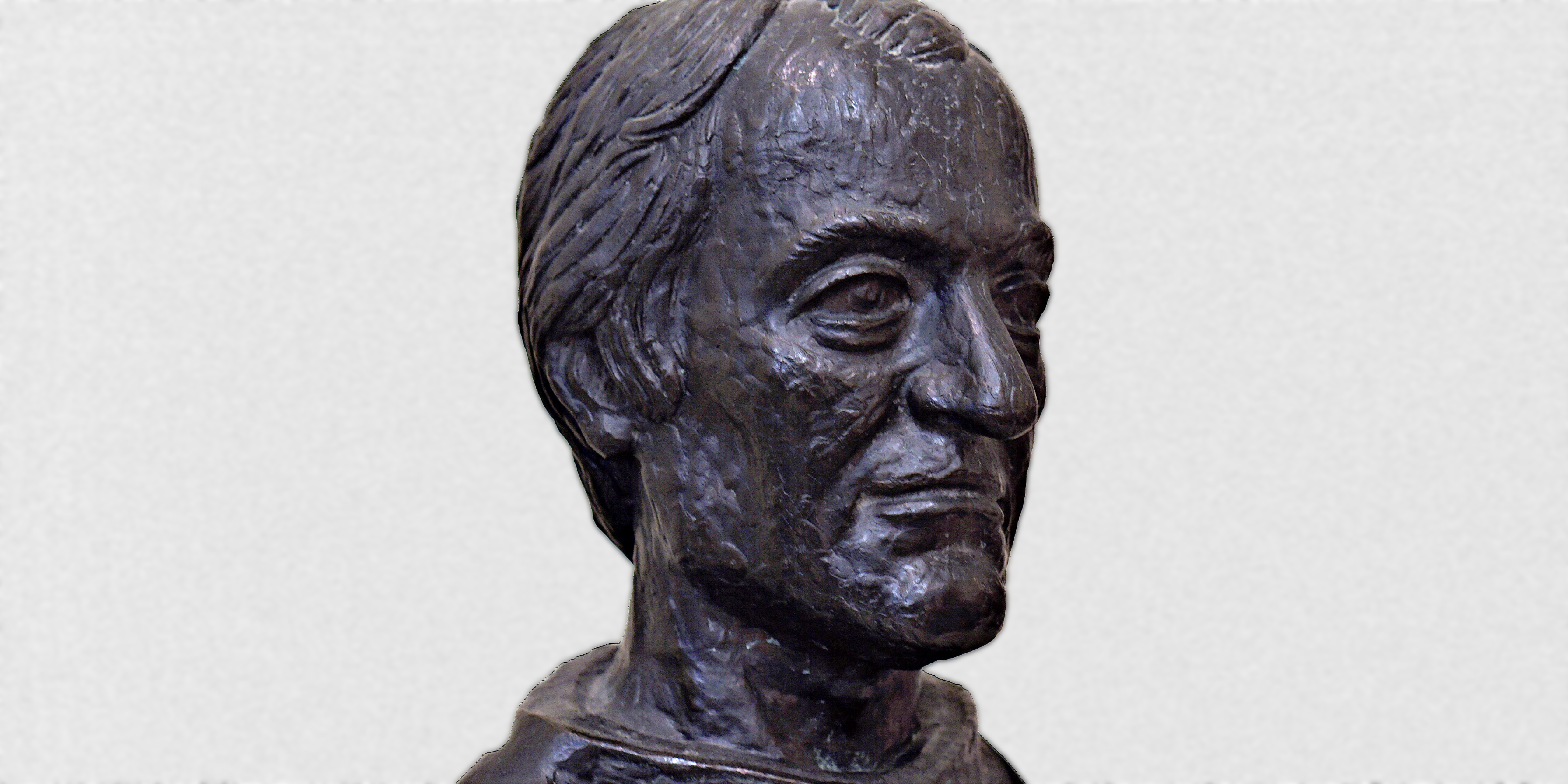

Though Fr. Richard is perhaps best remembered for his actions and words in the summer of 1805, they only serve as a microcosm of the virtuous, service-oriented life he embraced during his entire priesthood in Detroit.

Fr. Richard began his priestly duties in the midst of turbulent times. Just a couple years after his ordination as a Suplician priest in his native country of France in 1790, the French Revolution began to take a violent turn. Refusing to pledge allegiance to the new anti-Catholic government, Fr. Richard escaped the guillotine by boarding a ship bound for the United States.

His first assignment in America was in modern-day southwestern Illinois, serving as a missionary to the frontiersman and Indians in the region. In June 1798, Fr. Richard was then called to Ste. Anne’s in Detroit. Though the town’s population was less than a thousand upon his arrival, Detroit’s geographic position in the Great Lakes and its function as an important trading post for French settlers and indigenous people pointed to a promising future.

By all accounts, Fr. Richard was a driving force behind southeast Michigan’s Catholic community. The humble priest was seemingly everywhere at once, devoting his knowledge and wide-ranging skill set to serving his flock in every way imaginable. While visiting Detroit in the early 1800s, Bishop Joseph-Octave Plessis of Quebec took special note of Fr. Richard.

“He has the talent of doing, almost simultaneously, ten entirely different things,” penned Bishop Plessis. “Thoroughly learned in theology, he reaps his hay, gathers the fruits of his garden, manages a fishery fronting his lot, teaches mathematics to one young man, reading to another, devotes his time to mental prayer, establishes a printing press, confesses all his people, imports carding and spinning-wheels and looms to teach the women of his parish how to work, leaves not a single act of his parochial register unwritten, mounts an electrical machine, goes on sick calls at a very great distance, writes letters and receives others from all parts, preaches every Sunday and holyday [sic] both lengthily and learnedly…”

Fr. Richard’s priestly leadership was not just challenged by the 1805 fire. The War of 1812 brought global conflict and bloodshed to Ste. Anne’s doorstep. At the onset of the war in southeast Michigan, evidence points to the fact that Fr. Richard was operating a makeshift hospital for the sick and wounded. Detroit quickly fell into the hands of the British and its Native American allies on Aug. 16, 1812. Under Redcoat rule, Fr. Richard continued to loudly advocate on behalf of Detroit’s French and American community. Following the “River Raisin Massacre” in Frenchtown (modern-day Monroe), some sources suggest Ste. Anne’s priest might have paid the ransom for several men in Indian captivity. Because of his vocal pronouncements in favor of American governance, Fr. Richard was taken prisoner by British authorities in 1813.

Nevertheless, after just three weeks of imprisonment, he was freed. Popular legend has the leader of the Indian Confederacy, the Shawnee warrior-chieftain Tecumseh, demanding the release of Fr. Richard. Though this might be somewhat fanciful, there is no doubt that Ste. Anne’s pastor earned the respect of the indigenous people of the region. Fr. Richard made frequent visits to Native American villages around Detroit and beyond, sharing the Catholic faith with them and even imploring them to avoid the evils of the “liquor trade.” Perhaps most importantly to the various Indian tribes of the Great Lakes, the French priest contacted American government officials and voiced their concerns about being intimidated and cheated out of their ancestral lands. Later, Fr. Richard spearheaded education efforts for Native Americans in southeast Michigan.

A few years after the war ended, Fr. Richard turned his attention to the renovation of his parish, particularly the building of a new Ste. Anne’s Church. The cornerstone of the fifth church structure in the parish’s history was laid on June 11, 1818, exactly 13 years after the devastating fire in Detroit. It was going to be a costly and lengthy building project, especially considering many of Ste. Anne’s parishioners were still recovering financially from the recent conflict.

To offset the costs of construction, Fr. Richard took on a new endeavor of service. He ran for political office, in particular as a non-voting representative of the Territory of Michigan to the U.S. House of Representatives. Ste. Anne’s pastor promised to devote his new salary toward the construction of the church. His political opponent, prominent Detroit citizen John R. Williams, attempted to persuade Fr. Richard that he was unfit for the office. “Believe me,” Williams wrote, “you have talent for preaching the Gospel — hold to it — and to the French language — and you will assuredly will be useful to many good Christians. But I do not believe you will be able to get into the House of Representatives at Washington where they speak only English.”

Fr. Richard won the election and was readily accepted as an esteemed member of Congress. During his one term of service from 1823-1825, Fr. Richard defended the educational rights of Native Americans and even led the effort to create an improved road system connecting Detroit and Chicago. True to his promise, Fr. Richard’s emolument payments from his brief political career went to the construction of Ste. Anne’s. The upper portion of the church was finally completed in the late 1820s.

In 1832, Fr. Richard died doing what he had done for the past four decades of his life: serving the people of Detroit, Catholic and non-Catholic alike. That year, the now-forgotten Black Hawk War brought a cholera epidemic to the region. Mobilizing soldiers in early July spread the disease among Detroit’s residents. Several weeks later, Fr. Richard recorded that 51 of his parishioners had died since the beginning of the outbreak. Dozens of Detroiters were dying each week. Ste. Anne’s pastor quickly went to work at the city’s makeshift hospital, tending to the sick and dying. One Detroit resident described Fr. Richard’s constant activities during the epidemic. He could be “seen clothed in the robes of his high calling, pale and emaciated, with spectacles on his forehead and prayer book in his hand, going from house to house of his parishioners, encouraging the well, and administering spiritual consolation to the sick and dying.”

Just as the outbreak was dwindling in late August, Fr. Richard started to experience extreme fatigue and bouts of diarrhea, both telltale signs of cholera. Nonetheless, he continued his ministry, and was witnessed racing from house to house and hearing the confessions of parishioners in the midst of sickness. Fr. Richard's health ultimately took a turn for the worse, and on Sunday, Sept. 9, he could not get out of bed. In the coming days, he had his own confession heard and received last rites. Fr. Richard passed away on Thursday, Sept. 13, 1832, just after 3 p.m.

“Now O Lord, let thy servant depart in peace according to thy Word,” were the last words uttered by Fr. Richard. This final sentence was fitting for a priest who had loved and sacrificed so much for his physical and spiritual community. Though Fr. Richard is famously known as Detroit’s proverbial renaissance man, this priest’s primary goal was to be a servant to his Detroit flock. Whether it was after a tragic disaster, in the midst of troubling conflict, or even during his dying days, Fr. Richard always put the needs of his people and neighbors first.

Joe Boggs is a public high school teacher, historian and co-chairman of the Monroe Vicariate Evangelization and Catechesis Committee. Contact him at jboggs@pentacc.org.