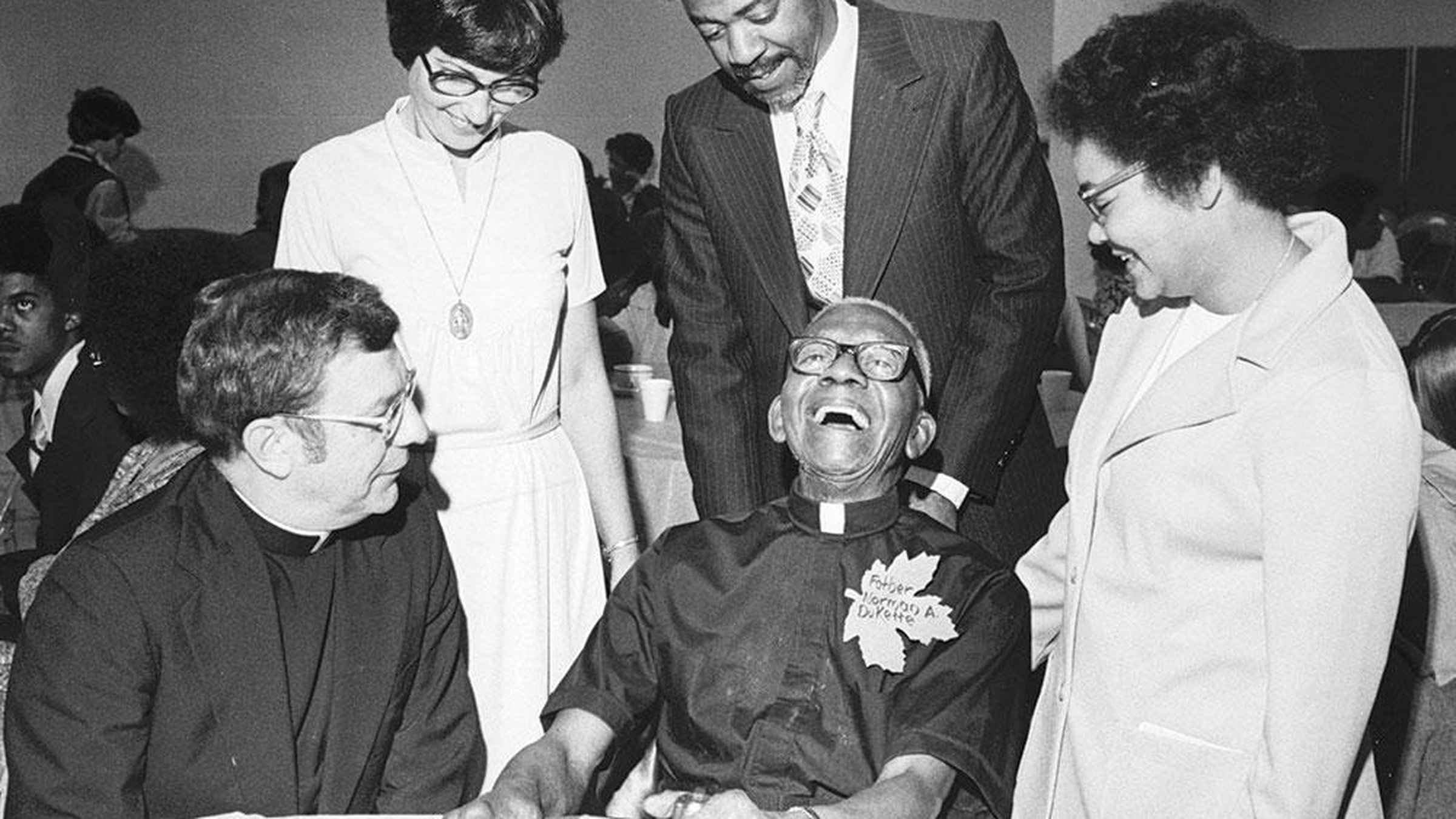

Ordained in 1926, Fr. DuKette endured prejudice, setbacks while serving Michigan's Black Catholic community for 43 years

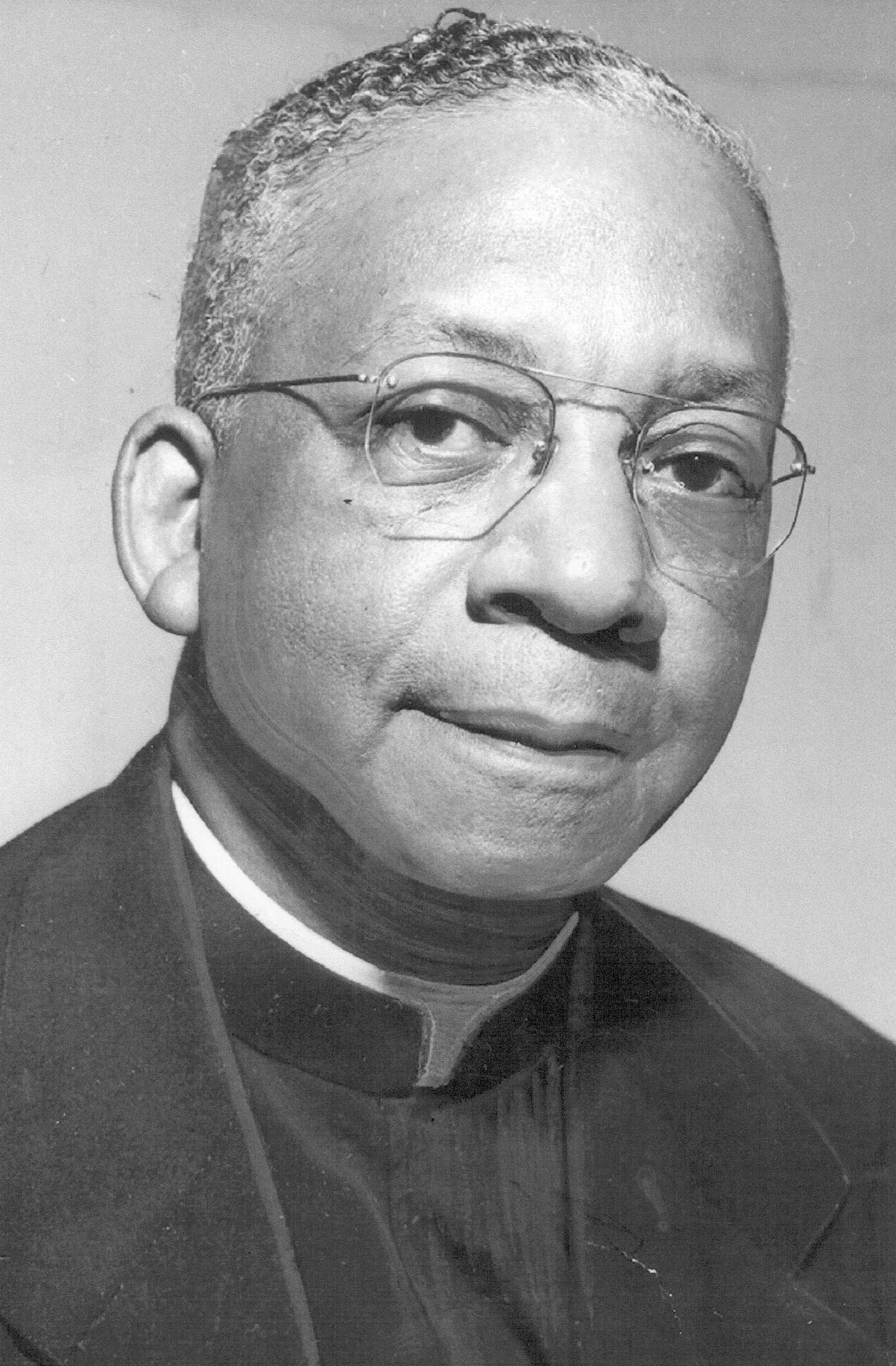

DETROIT — Almost 100 years ago, Fr. Norman DuKette made history when he was ordained among a class of 21 priests for the Diocese of Detroit.

While a class of 21 would be notable today for other reasons, Fr. DuKette's ordination made him the first African-American priest in Michigan — and only the fifth Black priest in the U.S. — shattering a barrier and beginning his legacy as one of the local Church's pioneering figures almost a century later.

While Fr. DuKette spent only two years in the city of Detroit — most of his ministry was spent in Flint, which at the time was part of the Detroit diocese — his lifetime of service continues to inspire Detroiters and African-American Catholics as a bedrock of faith in the local community.

Fr. DuKette was educated at Loras College in Dubuque, Iowa, before returning to his adopted hometown of Detroit to be ordained by Bishop Michael J. Gallagher in 1926. He was tasked a year later to establish St. Benedict the Moor Parish on 30th Street to minister to the Black community on Detroit’s west side, bounded by Livernois, Warren, West Grand Boulevard and Tireman.

Nancy Davis, Ph.D., associate professor of American History at DePaul University in Chicago, completed her doctoral work on the relationship between the African-American community and the Archdiocese of Detroit in the first half of the 20th century. Davis published an article in American Catholic Studies titled “Finding Voice: Revisiting Race and American Catholicism in Detroit,” which features Fr. DuKette’s brief tenure in Detroit.

“Learning about his life, Fr. DuKette was an extraordinary individual,” Davis told Detroit Catholic. “He was one of those types of people who come around every once in a while and are extremely gifted at what they are charged to do and are sincerely interested and committed to his congregation.”

Fr. DuKette was born Nov. 11, 1890, to John and Letitia DuKette in Washington, D.C., the 18th of a very large family of 27 children.

The family moved to Detroit in 1907, where Fr. DuKette's father worked for the government and ran a grocery store. After volunteering in the city's first Black mission, St. Peter Claver, the young Norman DuKette expressed interest in becoming a priest. After applying to many diocesan seminaries and religious orders — and fighting against prejudices any young Black prospective seminarian would face — he was finally accepted in 1916 to study at Loras Academy, where he graduated in 1918. He continued his studies at Columbia College, graduating in 1922.

After his ordination in 1926, Fr. DuKette was tasked with ministering to a Black community that was part of the first wave of the Great Migration, the early 20th century phenomenon of African-Americans moving from the rural South to the more industrialized North.

“He was an early part of the Great Migration,” Davis said. “Most of the Blacks who came early in the process were more educated than those who would come in the 1940s. The DuKette family came out of D.C., and that was a different experience to most of the Black people who moved to Detroit. D.C. was an area with a more Black middle class than that of Alabama or Mississippi. His parents were educated, and he was serving in an area with a more educated Black population that what we’d see later in Detroit.”

Fr. DuKette’s Washington, D.C., roots made him aware of the Harlem Renaissance and the civil rights movement in the 1920s, Davis said. He encouraged St. Benedict the Moor parishioners to be race conscious, leading to the creation of a chapter of the Federated Colored Catholics, which worked to record Black Catholic history and the Black Catholic experience. Even without a parish school, Fr. DuKette found tremendous success converting entire families to the faith.

But Fr. DuKette’s time at St. Benedict the Moor wasn’t to last long, as he was transferred to Flint in 1929 to establish Christ the King Parish, which became the cornerstone of the Black Catholic community in Flint.

Prior to Fr. DuKette’s transfer, an incident in 1929 highlighted the dangers and prejudices that continued to face young Black men in Detroit — even those called to serve at the altar, Davis said.

In May 1929, after attending a play at the University of Detroit, Fr. DuKette walked to a drugstore for aspirin because he had a terrible headache. Fr. DuKette wasn’t wearing his collar or cassock, so a police officer mistook him for a burglar and detained him.

“They apprehended him, questioned him there and indicated to him that they needed to take him down to the station for further questioning,” Davis said. “In fear of this incident being further publicized, he ran. And instead of running after him, they shot him in the leg, and he was taken to the hospital.”

Fr. DuKette was subsequently transferred to Flint, but Davis and others believe his influence in the city of Detroit could have been greater had he remained.

“The Black Catholic community in Detroit would have been much larger had he not been moved,” Davis said. “He would have continued to build and build and build. But Flint was lucky to have him.”

Fr. DuKette’s pastoral skills followed him to Flint, where he helped create Christ the King Parish “from out of nothing” as the center of the Black Catholic community, serving the growing number of African-Americans who were moving to the city, attracted by the booming automobile industry and the desegrated General Motors plants.

Fr. DuKette remained at the parish for 41 years until his retirement in 1970.

“Parishioners from Christ the King that I talked to always talk about his door-to-door visits,” Davis said. “He endeared these people to the Church. Remember, being a Black Catholic was very difficult in the 20th century, with all the racism, the colorism, preferring light-skinned Blacks over dark-skinned Blacks. Detroit, and later Flint, were working-class cities with Black populations that weren’t traditionally Catholic. In Detroit, you had factory workers from Alabama. The treatment they received was awful from the Church, so Fr. DuKette knew what they were going through. He was a genuine Black person who understood racism.”

Fr. DuKette’s gentle example, overcoming prejudice and meeting parishioners where they were, gave him the ability to convert families and cement his legacy as a bridge-builder, Davis said.

“He understood the Black Catholic experience and wasn’t afraid of it,” Davis said. “I think his sincerity, his kindness were key. The community he served was looking for someone who could respond to them and someone who knew the African-American experience, and they got that in Fr. DuKette.”

St. Benedict the Moor Parish never reached the same level of activism and prominence in the area after Fr. DuKette left, Davis said, and the Marianhill Fathers, a German religious order with experience in Africa, took over the parish. The parish later experienced a resurgence when the Holy Ghost Fathers took it over five years later, after much protesting from parishioners.

But Fr. DuKette’s brief time at St. Benedict the Moor established the parish as a center for Black consciousness in the decades to come, Davis added.

“Detroit had a very active Black Catholic protest movement in the 1960s, despite not having a large Black Catholic community, and that is in part because of the labor movement, but (also) because Fr. DuKette, only here for two years, instilled that in the community,” Davis said.

Davis said it is beyond doubt that Fr. DuKette had great impact on the Black Catholic community in Flint, but she wonders what it would have been like to have Detroit’s first Black Catholic priest stay in the Motor City a little longer.

“I’m glad he was able to show his greatness through Christ the King; the people loved him so much, that appreciation of all he went through,” Davis said. “But you can hear in Detroit, from the people I interviewed, the letters of appreciation from his St. Benedict parishioners, how much they loved him. But fortunately, because of Flint, we get to hear it, feel it, and that is the great thing about (his time in) Flint: we’re able to actualize who he was as a person.”

An earlier version of this story misidentified the location of Loras College.

Copy Permalink

History Black Catholic ministry