From a simple chapel in the wilderness to a grand basilica in 2020, Detroit's oldest parish has a timeless story to tell

DETROIT — When one walks into Ste. Anne Church, they are stepping into history.

Built in 1886 and consecrated in 1887, the neo-Gothic church on the corner of Ste. Anne and Lafayette in southwest Detroit — which Pope Francis announced March 1 would become a basilica — has a history dates back to the city’s founding.

Want local Catholic news? Sign up for Detroit Catholic's daily or weekly digest

The church's twin spires overlook a riverbank where French general Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac and a party of French explorers — including two priests — landed on July 24, 1701, to establish Detroit, French for “by the straight.”

Two days later, on July 26, 1701 — the feast of Ste. Anne — the explorers built a simple wooden hut inside the palisade walls of Fort Pontchartrain du Detroit to offer up the Eucharist and give thanks to God for their safe voyage.

Bob Wayner, a parishioner at Ste. Anne and docent who gives tours of the iconic parish, said the first Ste. Anne Church was as simple as it was reverent.

“This area was a wilderness when Cadillac came,” Wayner told Detroit Catholic. “The Native Americans, of course, were here, but there was no established settlement, just an area used for hunting and fishing. Cadillac wanted to control the area for France, controlling the hunting and fur trade, so he built a fort for that purpose.”

Wayner said faith was important to the explorers, so when they built the first church in Detroit, they named it after St. Anne, both in honor of her feast and because of the French people's strong devotion to her.

Within the simple wooden walls of Fort Pontchartrain, Ste. Anne was a place where Masses, baptisms, wedding and funerals kept the pioneers grounded in the higher things of life.

The parish’s records date back to 1703, when Cadillac’s daughter was baptized. Prior records were destroyed in a fire, a common occurrence in the wooden settlement, where Native American attacks were common. Indeed, the first six Ste. Anne churches were wooden structures inside or just outside the fort’s wall, destroyed by fire in skirmishes between Native Americans and various European forces.

The final wooden Ste. Anne building was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1805, when the parish’s pastor, Fr. Gabriel Richard, penned the city’s now-famous motto: “We hope for better things; it will arise from the ashes.”

“Fr. Gabriel Richard was an incredible man, so important in Detroit history as well as Michigan history,” Wayner said. “He was a young priest, newly ordained in France when he fled the French Revolution. He ended up west, near the Mississippi River, as a wilderness priest before being transferred to Detroit in 1798.”

A pioneering priest

Fr. Richard served as Ste. Anne’s pastor for 30 years, bringing the first printing press to the city to print religious books for Mass, starting an integrated school for both white and Native American children — a concept unheard of at the time — and founding the University of Michigan.

“Fr. Richard represented the Michigan Territory in Congress before we were a state,” Wayner said. “He got a road built from Detroit to Chicago, a plank road with federal funding. That road is still out there: it’s Michigan Avenue. He was a friend to the Native Americans, and they invited him to sit on treaty negotiations because they trusted him.”

Wayner said Fr. Richard encouraged Detroiters to stay loyal to the United States during the War of 1812 after the British sacked the city. The British imprisoned Fr. Richard, transporting him across the river, but the crown’s principal ally in the conflict, Chief Tecumseh of the Shawnee Indians — refused to fight until Fr. Richard was released.

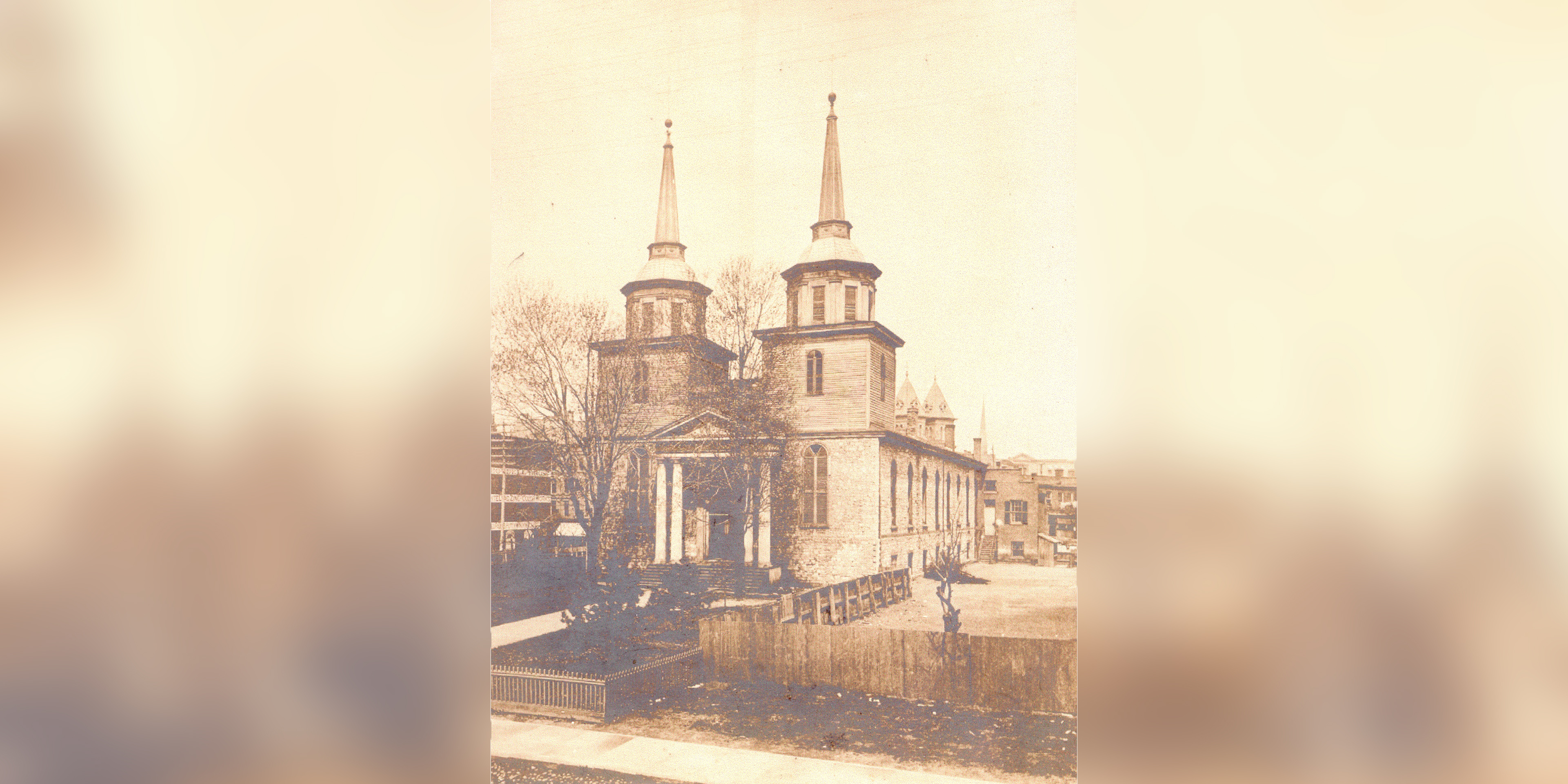

After the war, the city went on constructing a more permanent Ste. Anne Church to replace the one that burned in 1805. In 1818, the cornerstone of the “stone church” on the corner of Larned and Bates in downtown Detroit was laid, serving as the first “permanent church” in the city.

Elements of the 1818 “stone church” are still present in the current, 1886-built church.

“Here at Ste Anne, we have the oldest stained glass in the city, the top windows of the church building, that were part of the 1818 church,” Wayner said. “The statue of St. Anne at the Ste. Anne shrine, along with the Sacred Heart of Jesus statue, were part of the 1818 church. The hand-carved beautiful altar rail, the sanctuary lamp and the altar Gabriel Richard used is now in our chapel.”

Fr. Richard ministered from Ste. Anne — with parish boundaries that encompassed of all of Michigan and Wisconsin — until his death in 1832 from cholera after he contracted the disease while caring for the sick in a nursing home he established.

“When I think about the St. Anne statue at the shrine, I think, ‘Gabriel Richard prayed at this statue; he distributed Communion at this altar rail,’” Wayner said. “The most amazing thing is, they brought his body here. When he died in 1832, he was held in such high esteem, they buried him in the floor of his church as a sign of honor and respect.”

Eyes raised to heaven

With the “stone church,” Ste. Anne was amidst the hustle and bustle of downtown Detroit, serving as Detroit’s first cathedral from 1833 to 1848. But as the city grew, downtown property became more and more valuable, and the parish, looking to serve its growing flock, sold the original Ste. Anne property and moved in 1886 to its current location on the corner of Lafayette and Ste. Anne in southwest Detroit.

The parish split up the possessions of the stone church, with half being incorporated into the parish’s eighth church, and the other half going to St. Joachim Parish, on the corner of East Fort and Dubois, which served French Catholics on the city’s east side.

The new, neo-Gothic church designed by Albert E. French had the parish’s original 1818 cornerstone embedded in one of its bell towers and the body of Fr. Richard interred below the sanctuary. Fr. Richard's remains — along with the altar where he celebrated Mass — were moved in 1976 after the parish received a grant to renovate its chapel to make it reflect the 1818 stone church.

In the “new” Ste. Anne, the neo-Gothic church is designed to draw the visitor’s gaze towards heaven, Wayner said. Everything from the carvings on the pews to the shape of its windows are pointed up to the deep blue ceiling that’s decorated with golden stars and moons, mimicking the heavenly skies.

“Everything you see draws your eyes up to heaven,” Wayner said. “It all has a point; all the archways have a point. All the stained-glass windows have a point, all designed to lift your eyes to heaven. This church is meant to be heaven on earth, where we are surrounded by the saints with all these beautiful windows and statues, and Jesus is alive in the tabernacle.”

The church is decorated with French fleurs-de-lis and windows donated by some of Detroit’s oldest families, bearing names like Beaubien, Groesbeck and Campau.

Demographics change, but spirit remains

By the time the parish moved to southwest Detroit, the French presence had already started to dwindle, replaced by Irish immigrants moving into Detroit’s west side. By the 1940, Hispanic immigrants moved into the area, attracted by jobs in the automotive and steel industries.

“Ste. Anne Church, this building, has been the anchor in the neighborhood through all those changes,” Wayner said. “This is something that hasn’t changed. Even though the ethnicity of the residents has changed — we’re largely a Hispanic parish now — but the spirit hasn’t changed.”

Ste. Anne was at risk of closing in the 1960s, but the influx of Hispanic parishioners kept the historic parish open. The Hispanic congregation began worshiping at Ste. Anne’s in the 1940s in the chapel, but now the most-attended Mass is the 10 a.m. Sunday morning Mass in Spanish in the main church.

The parish has adopted several Hispanic customs, from celebrating Las Posadas during Advent to decorating an altar of Dia de los Muertos (“Day of the Dead”) on All Souls Day.

But the parish keeps its roots alive each July with its annual novena to St. Anne — which has been celebrated in Detroit for more than 100 years. The yearly celebration begins July 17 as the parish hosts Masses and devotions that celebrate various cultures found in Metro Detroit, from French and Spanish to Irish, Polish and Chaldean.

While French Catholics aren't nearly as prominent in Detroit as they once were, Ste. Anne might be one of the last bastions of French heritage in the city. Each fall, a French historical group hosts “Rendez-vous,” an annual celebration of French-Canadian and Native American history.

A connection to the past

Today, thousands of people annually come through the doors of Ste. Anne, where Wayner and other docents give guided tours of the parish and its place in history.

“I’m excited about sharing the history,” Wayner said. “Last Sunday, there was a family at the 10 a.m. Mass, and I didn’t recognize them and they were looking up. When people are looking around like that, you know they are a visitor, and they can’t believe how beautiful it is. So I welcomed them and took them into the chapel to see the tomb of Fr. Richard. And every time, people say they didn’t know this was here.”

Groups of catechism students, seniors and Detroit sightseers often make it a point to visit Ste. Anne, to take in a beauty that transcends the centuries.

As the second-oldest continuously operating Roman Catholic parish in the United States, Wayner says modern-day parishioners have an incredible connection with the first souls who gave thanks to God on Detroit’s shores almost 319 years ago.

“We are not a rich parish, financially, but the spirit here is amazing,” Wayner said. “Think about all the people who came all those years before, the stewards of the parish, and we are the stewards now.”

As Wayner gazes up at the ceiling of Ste. Anne, he knows he's looking at the same stars and moons so many earlier generations saw. He thinks of his own prayers that have been answered here — his wife was originally a Ste. Anne parishioner when they met, and they were married in the church. He also thinks of the prayers of so many others, including the abandoned crutches left at Ste. Anne’s shrine in gratitude of a healing bestowed.

When confirmation classes make the tour, he points out all the details that have been left for the next generation to discover, to cherish, and to pass on to the next generation whose roots are embedded deep in Detroit’s soil and its soul.

“When I talk to our catechism kids, and the confirmations students at Ste. Anne Parish, I always have them think about 1701, how kids were getting baptized at Ste. Anne Parish,” Wayner said. “How through the years — the confirmation, the weddings, the baptisms and funerals — you are part of that Detroit history now. You are getting a real connection to the history of our faith and a connection to all the faithful who came before you, who called this place home.”

Daniel Meloy is a staff reporter for Detroit Catholic. To receive Detroit Catholic email updates in your inbox daily, weekly or monthly, subscribe to our e-newsletter.