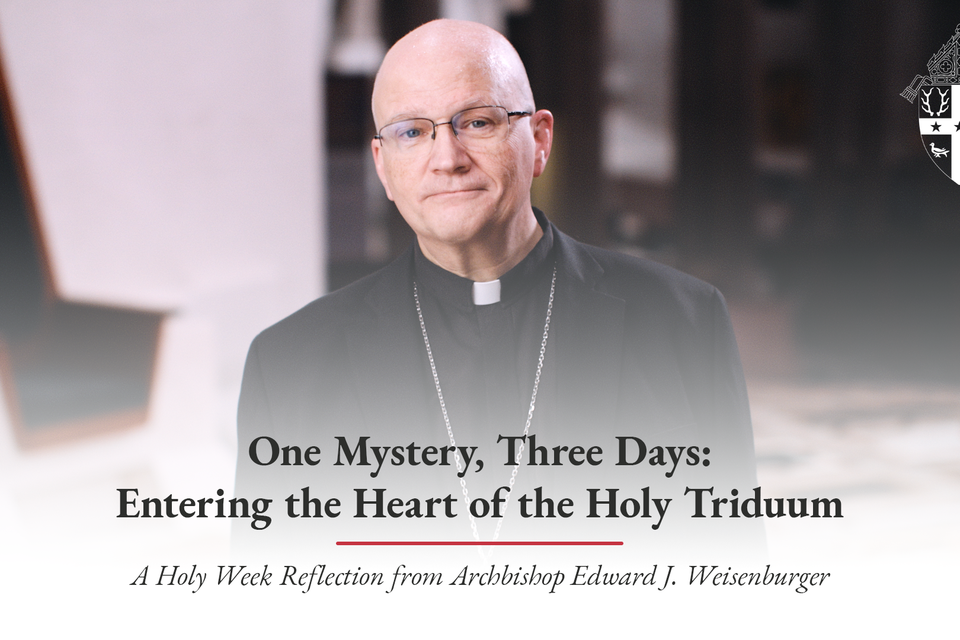

In introductory interview, Detroit's new shepherd shares about his roots, vocation and hopes for a bright future in Motor City

DETROIT — Once in Salina. Once in Tucson. Once in Detroit.

Three times, Archbishop Edward J. Weisenburger has received a call to shepherd a new diocese, and three times, he’s said yes.

Each time he’s taken his seat upon his new cathedra — the moment when a new bishop receives authority in his diocese — he’s felt the weight and solemnity of the moment.

“I’m a canon lawyer, in addition to being a priest and bishop,” Archbishop Weisenburger told Detroit Catholic during a recent sit-down interview. “When a new bishop sits down in that chair, that’s the time in canon law it’s recognized that he’s received his role of ministry in that diocese. It’s a very pivotal moment. It’s, for me, been a very sacred moment.”

While Archbishop Weisenburger, 64, has received blessings in each of his three episcopal stops, he hopes his March 18 installation in Detroit will be “the last,” because, he says, “I am definitely home.”

In the three weeks since the inauguration of his ministry as Detroit’s sixth archbishop, Archbishop Weisenburger has embarked upon a crisscross tour of his new home, visiting parishes and schools, greeting local Catholics and celebrating liturgies all over Metro Detroit.

“I’m learning a lot about the archdiocese,” Archbishop Weisenburger said. “I have people around me who are funneling information to me constantly. It’s good to absorb that information in appropriate and reasonable ways so that then I can be of better service to the people.”

The people of the Archdiocese of Detroit have been “exceedingly warm and gracious,” he added.

In his first few weeks, Archbishop Weisenburger has also spent time with the local Hispanic community, visiting Holy Redeemer Parish in Detroit, St. Damien of Molokai Parish in Pontiac and celebrating Mass during the archdiocese’s annual Hispanic Men’s Conference, among other stops.

“I knew I’d be using a lot of Spanish when I went to Arizona, and I’m finding I’m already using no small amount of Spanish right here in Detroit, and that pleases me,” Archbishop Weisenburger said. “I’m very grateful for the warmth of the Hispanic community. I’m getting to know more and more people every day.”

During the wide-ranging interview, Archbishop Weisenburger spoke with Detroit Catholic about his upbringing, vocation story and the blessings he’s experienced as a priest and bishop in Oklahoma, Kansas and Arizona, as well as his hopes for the years ahead in Detroit.

A humble upbringing

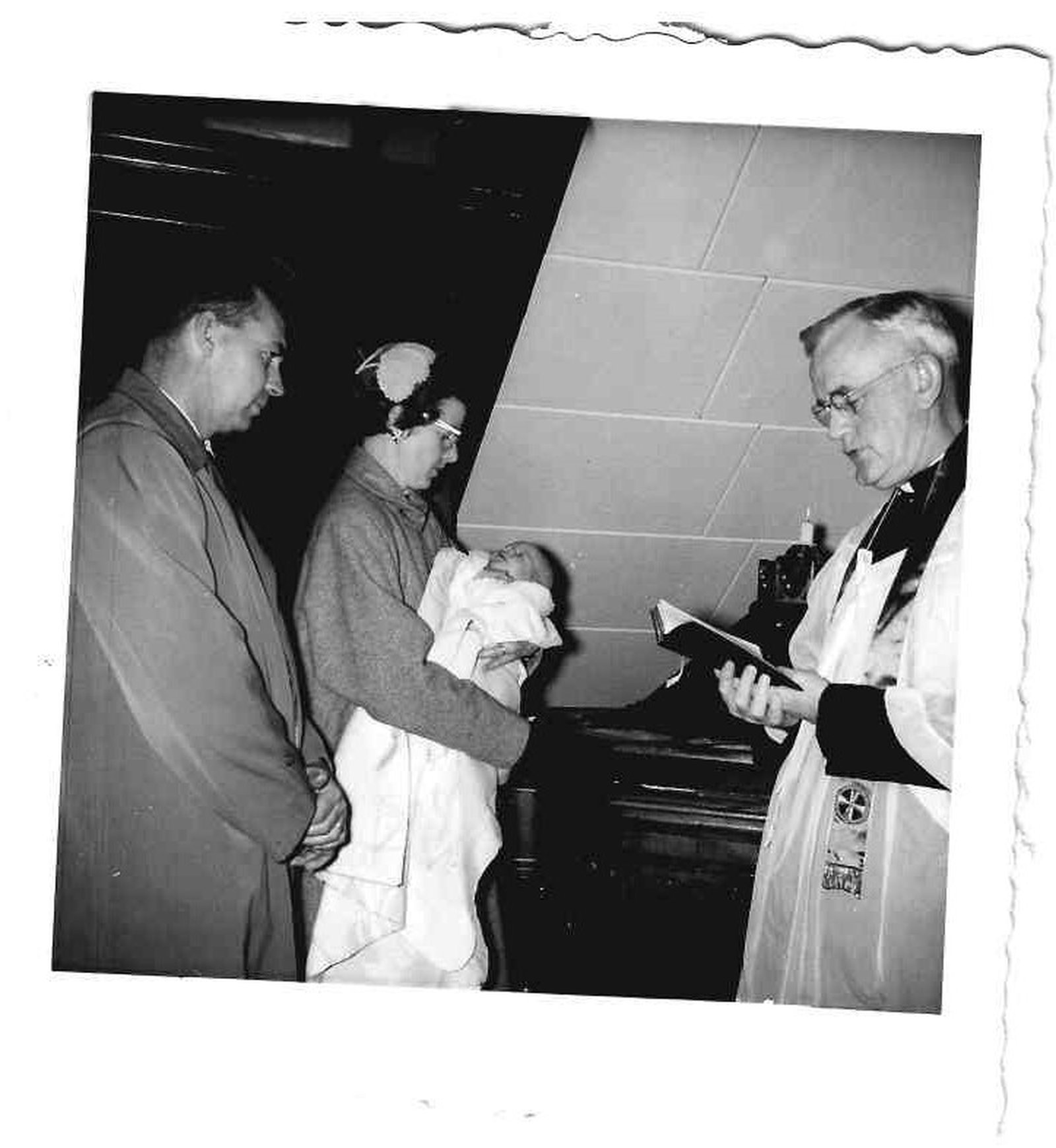

Although born in Alton, Illinois, Archbishop Weisenburger spent much of his childhood growing up on the sweeping plains of Kansas and Oklahoma.

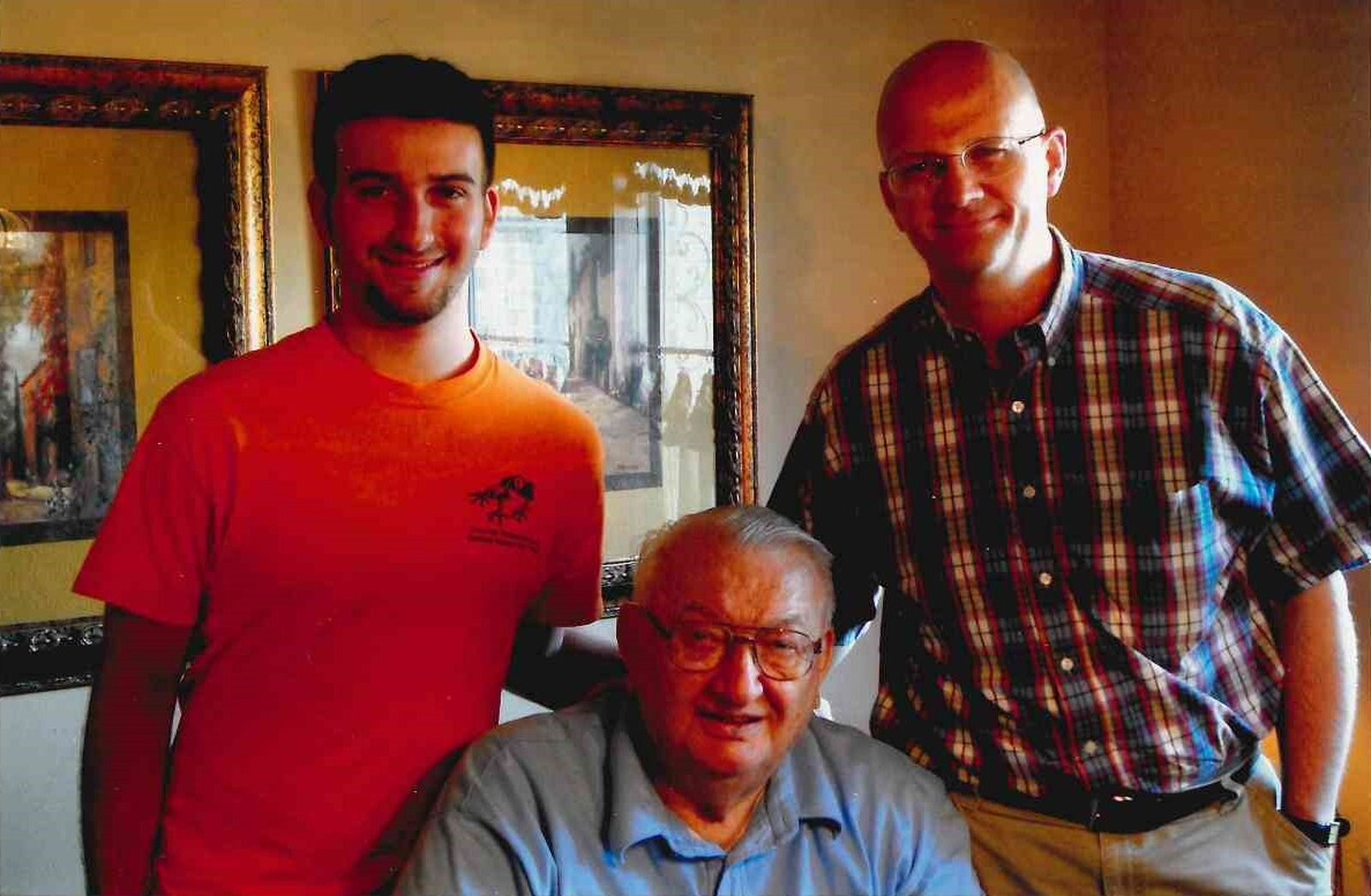

His father, Edward John Weisenburger, was a military officer and a World War II veteran who later went on to become an Army pilot and a flight instructor during Archbishop Weisenburger’s childhood.

Two separate years, in 1964 and 1967, his father flew Army helicopters in Vietnam during the war, which were “tremendously stressful times,” Archbishop Weisenburger recalled.

“In those days, a serviceman or servicewoman would put their family in a safe place so that if they didn’t make it home, it would be less traumatic,” the archbishop said. “We were always taken back to live those two years where my mother was from in western Kansas, where I would later become a bishop.”

His mother, Asella (Walters) Weisenburger, was from the tiny wheat farming village of Catharine, Kansas, a community of less than 200 people just a stone’s throw from the town of Hays, where she and Edward John met and were later married.

“We were surrounded by much love and affection there,” recalled Archbishop Weisenburger, whose family belonged to St. Joseph Church in Hays, where he attended second grade. “That school, that church and that community really circled the wagons around us and cared for us both of those years.”

He fondly remembers the influence of his maternal grandmother, Mathilda Walters, who lived with the family during their second stay in Hays. Her deep, joyful faith and devoted prayer life rubbed off on the young Edward.

“She was a person of profound joy despite her tremendous illness and old age,” Archbishop Weisenburger said. “She had tremendous osteoporosis and arthritis and was very crippled, but she was perhaps the most joyful person I’ve ever known in my life. You don't even perceive the impact it's having on you, the joy she felt out of her faith.”

Growing up, faith “was woven into the DNA of our lives,” the archbishop said.

“My father, as well as my mother, were marvelous Catholics,” Archbishop Weisenburger said, adding his father converted shortly after meeting his mother. “He was a state officer in the Knights of Columbus, very active in the parish council, lectoring and would do all of those things. We were just one of those Catholic families that was very involved in the Church.”

Vocation from an early age

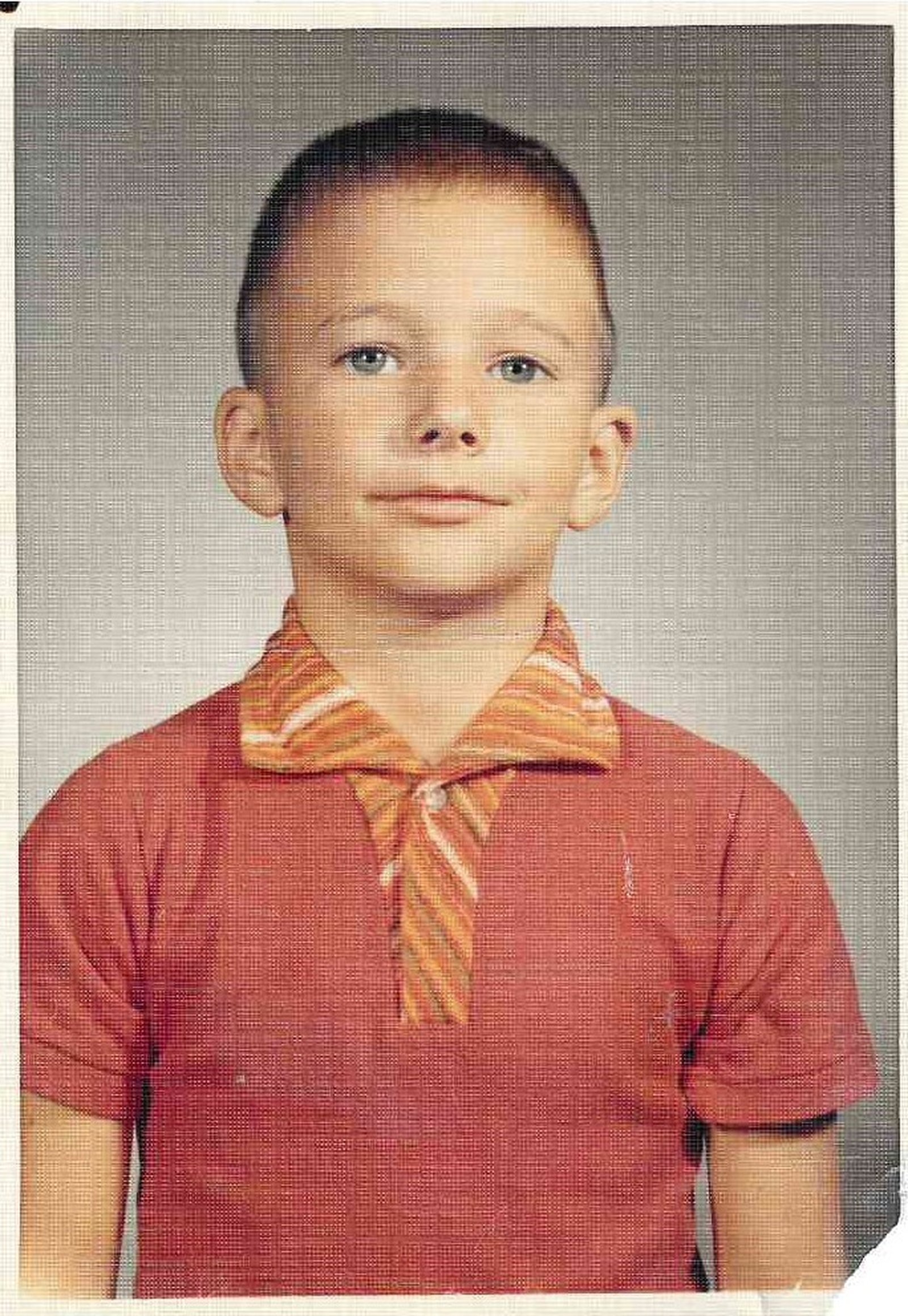

Apart from their time in Hays, most of Archbishop Weisenburger’s formative years were spent in Lawton, Oklahoma, a town of about 60,000 near Fort Sill, a U.S. Army post. Like in Hays, the family was very active in their faith, and soon, the young Edward began to hear God calling him to a future in the Church.

When Archbishop Weisenburger says his call to the priesthood began from an early age, he’s not exaggerating. As he tells it, he had no backup plan.

“It was never, ‘Do I want to be a fireman or a priest? Do I want to be a farmer, or a teacher, or a businessman, or go into the Army?’ I never had a plan B,” he said. “I love hearing priests’ vocation stories coming from all facets of life, but I am one of those rare cases these days where, I think from childhood, I just had this sense that that was it.”

Like many priests, the archbishop cites serving at Mass as a pivotal influence on his vocation.

“Fr. (James) Stafford, my pastor for the majority of my time (in Lawton), was gracious and kind to me and encouraged me,” Archbishop Weisenburger said. “I always joke I was 18 years old when I graduated from high school, but I’d been a Mass server for 20.”

He remembers the first time he served at the altar like it was yesterday.

“My dad drove me over after work for the afternoon Mass, and it was my first time to serve Mass. I remember putting on the cassock and surplice, and I looked in the mirror, and it was like a piece of TNT went off,” he said. “It was just like, ‘Wow, this is what you’re supposed to be doing.’ It was a really powerful moment as an 8- or 9-year-old.”

Upon graduating high school in 1979, he enrolled in Conception Seminary College in Missouri, followed by four years at the American College Seminary at the Catholic University of Louvain in Belgium, where he got a “world class” theology education.

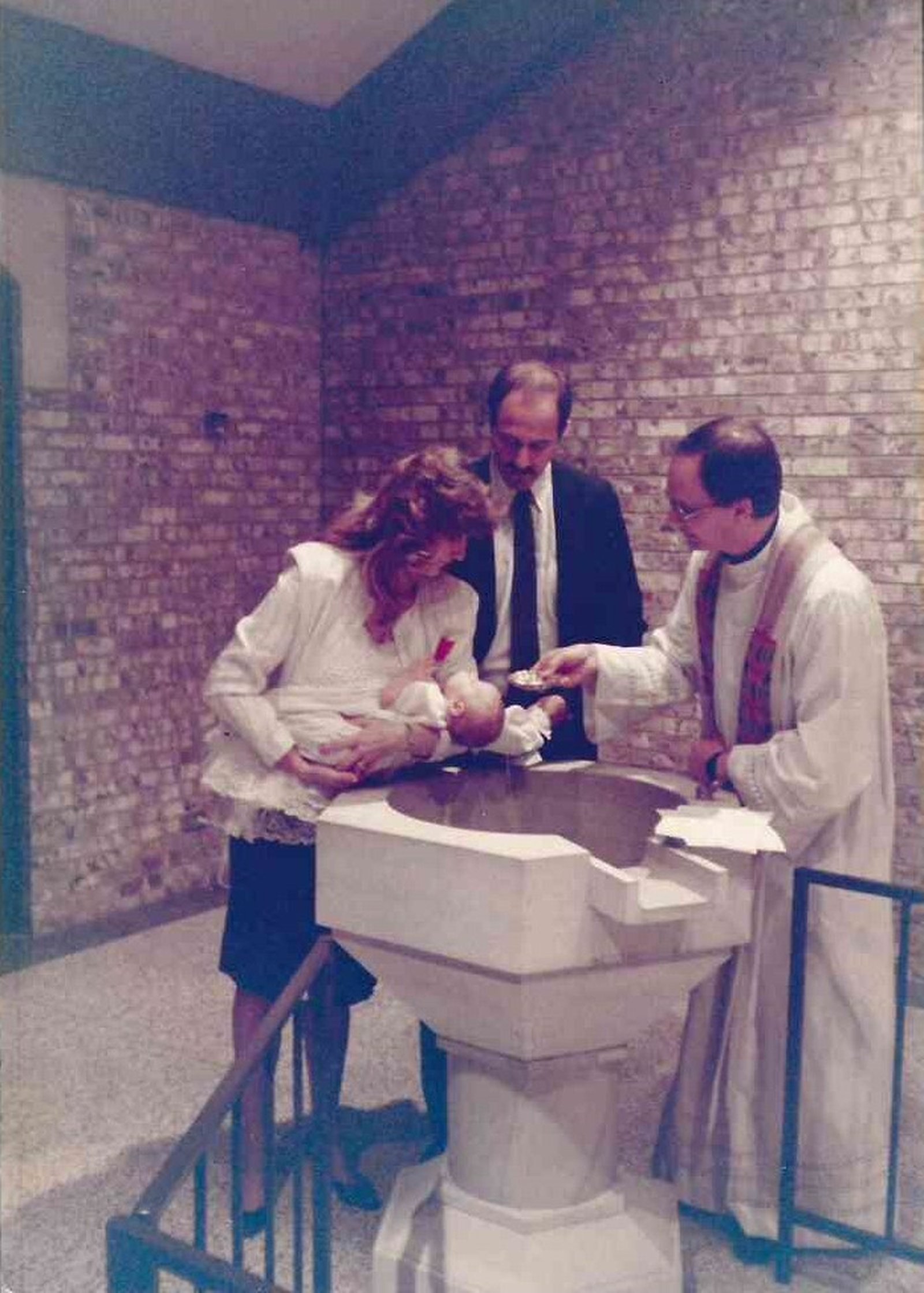

In 1987, he returned home and was ordained a priest for the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City on Dec. 19. His first three years in parish ministry were spent in Ponca City, Oklahoma.

One of the most powerful lessons he learned as a young priest was how to be adaptable, he said.

“I always say you learn far more about being a priest on the job than you do in all the years of seminary. A young priest’s first assignment is just so critical. I had a marvelous first pastor, Fr. Ernie Flusche, a wonderful man,” Archbishop Weisenburger said.

“Ministry in the Church, especially leadership ministries, evolve in accord with the needs of the people and the issues of the day," he added. "I sometimes sense the happiest priests, the most joyful priests, who tend to be an encouragement for others, are those who are able to adapt to the real needs of the community.”

Ministry of presence

One of the earliest tests of then-Fr. Weisenburger’s ability to adapt came on April 19, 1995, when, on a quiet Wednesday morning, Oklahoma City was shaken to its core.

The bombing of the Murrah Federal Building — the single deadliest act of homegrown terrorism in U.S. history — left 168 people dead and injured 680 more, instantly changing life for all Oklahomans. After earning his canon law degree from the University of St. Paul in Ottawa, then-Fr. Weisenburger was working at the time in the archdiocesan chancery downtown, “and suddenly the building shook,” he recalled.

“Our archbishop was away, but our retired archbishop was there, so I dashed over to his house, grabbed him and drove to the Catholic hospital, which was less than a mile from the bombing,” Archbishop Weisenburger said. “It had blown out some of the windows in the hospital, but we spent about 48 hours as victims were being brought in. It was a real crisis, just a horrific, horrific act of homegrown national terrorism."

In the aftermath, he volunteered to serve as an on-site chaplain as rescue workers dug through the rubble for survivors.

“It was extremely complicated because of the risk of collapsing more and perhaps killing more people,” he said. “It was very painful.”

As he stood by, few workers approached him, and the feeling that he should be doing more — anything more — began to overwhelm him. “I found myself sort of frustrated," Archbishop Weisenburger said. "I realized I felt like I hadn’t done much.”

Going home that night, he spoke with an older priest about his experience. The priest counseled him to return the next day with a rosary and a pyx filled with the Eucharist, and to "let them see you praying," he recalled. So he did. As he stood and prayed, occasionally, a worker would look over, exhausted, before continuing their search. Occasionally, he'd offer the Eucharist. His presence — and, more importantly, the presence of Jesus — seemed to bring them comfort.

“That was the first time in my life I learned the ministry of presence,” Archbishop Weisenburger said. “They didn’t need to come and talk to me. They really just needed me to be there, and any priest would’ve worked. And that’s the marvel of the priesthood — when it was all over, as painful as it was, it was an incredible honor to be of just that little service to people who were doing such dangerous work with so much devotion and care.”

If he needed a reminder of the power of presence, his next assignment would confirm it.

Later that year, then-Fr. Weisenburger was assigned pastor of Holy Trinity Parish in Okarche, the home parish of Blessed Stanley Rother, who, in 1981, was martyred in Guatemala for his refusal to abandon his flock.

A priest of Oklahoma City, Fr. Rother was sent to serve the archdiocese’s mission parish in Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala, ministering to the local Tz’utujil tribe. Despite struggling in seminary, he learned to speak and write Tz’utujil, a challenging Mayan dialect, as well as Spanish, and even translated the Gospel into the native language. As a civil war erupted in the Central American nation, however, Fr. Rother was wanted by the death squads, and he was brought back to Oklahoma City in 1981 for his own safety.

After a few weeks, Fr. Rother grew uneasy, and pleaded with his archbishop to return to Guatemala. It would be his last trip.

“The archbishop told him, ‘You’ll be killed if you go back.’ But it was getting close to Holy Week, and Fr. Rother said, ‘I can’t leave 50,000 people without the sacraments.’ And he went back, and he gave his life in just a magnificent, loving way,” Archbishop Weisenburger said. “He’s a real icon for us in Oklahoma and increasingly across the nation.”

While serving at Holy Trinity, Archbishop Weisenburger gained a front-row seat to a life of humility and holiness that embodied Oklahoman Catholic spirituality.

“I actually know Blessed Stanley’s family quite well,” Archbishop Weisenburger said. “His sister is a religious sister of the Adorers of the Precious Blood, Sr. Marita Rother. I hired her to be principal of the elementary school right there in Okarche, so we became very good friends. I presided over his father’s funeral. I learned much about western Oklahoma farming right there in Okarche.”

Both because of his familiarity with the family and because of his canon law background, Archbishop Weisenburger was eventually asked to serve as promoter of justice for Blessed Stanley’s canonization cause, a role that used to be called "devil's advocate."

“The reason it was called that — and certainly they’ve changed the name — is because my role was to make sure the real questions were being asked, not just the ‘nice’ questions,” Archbishop Weisenburger said, adding he's been to Guatemala at least "10 or 12 times" over the years. “Someone had to do it with that kind of training.”

“Fortunately, I failed,” he laughed. “I succeeded in my endeavor of asking all the pointed, direct questions, and then I rejoiced when the Holy See approved him for beatification (in 2017).”

Becoming a bishop

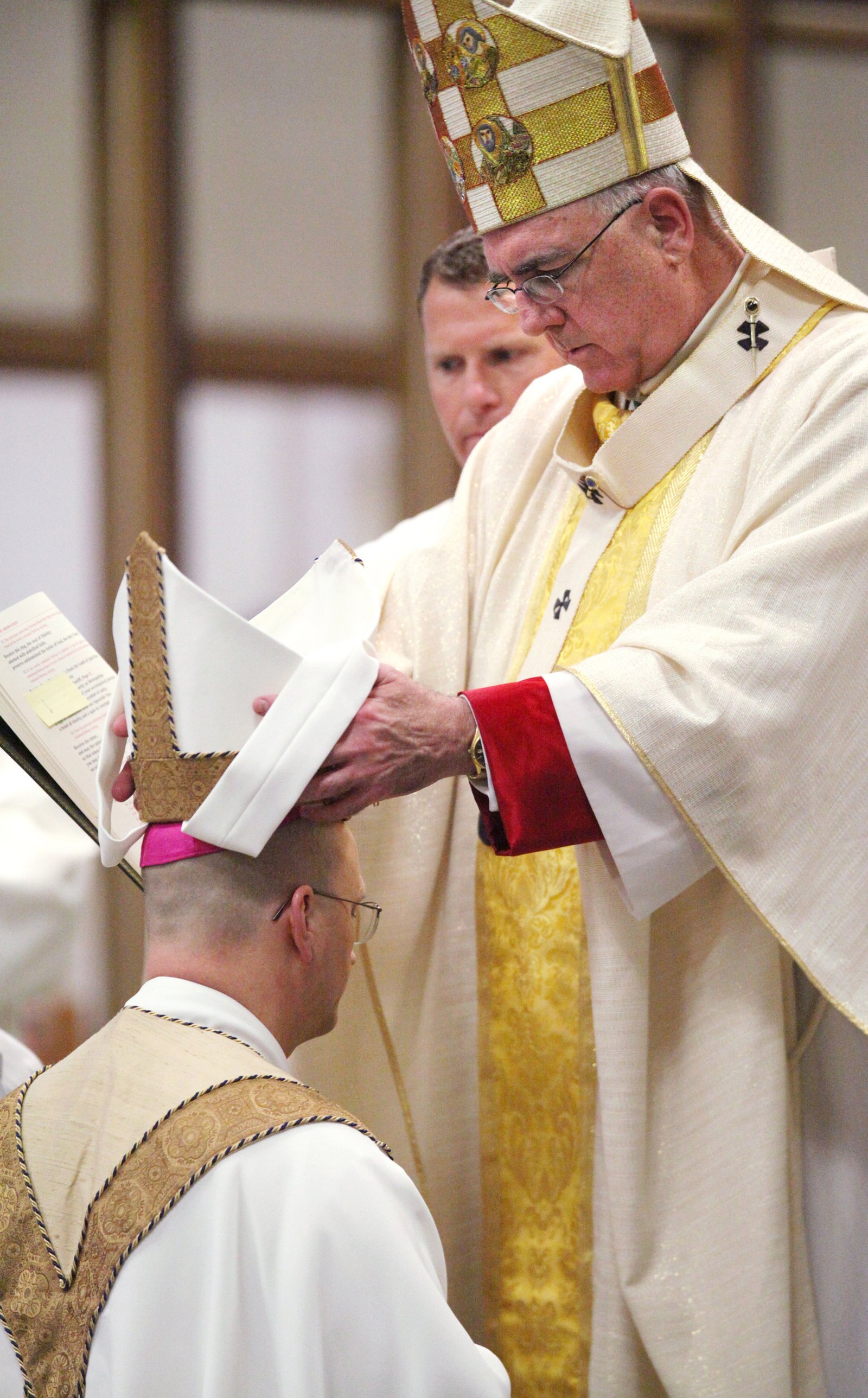

Like all bishops are, Archbishop Weisenburger was surprised when he got the call in 2012 that Pope Benedict XVI was naming him a bishop.

He was even more surprised to find out where he was being sent.

Becoming bishop of Salina, Kansas, wasn’t itself so much of a homecoming, but returning to the small farming communities of Hays and Catharine — about 90 miles west — as their bishop was a surreal, nostalgic blessing.

“Going back to that little village where my mother had been born, my grandparents are buried — going back to that pristine, beautiful little church, which for us was always the roots, that was incredible,” Archbishop Weisenburger said. “To go back to that church as its bishop, that was very moving and it's still moving. To me, that was a homecoming.”

Another unexpected blessing was the opportunity meet Pope Benedict just weeks after his appointment — even before his ordination — as the bishops of his new region traveled to Rome for their "ad limina" visits. When it was his turn to shake the pope’s hand, he smiled, introduced himself and told the pope he had just been appointed to Salina.

“He was so kind,” Archbishop Weisenburger recalled. “He asked me, ‘When will you be ordained?’ When I said May 1, he became very animated and said, ‘That’s my feast day.’ Remember, his baptismal name is Joseph, and May 1 is the feast of St. Joseph. And he said, ‘I will remember you this year on my feast day.’ And I thought, what a great kindness.”

After five fruitful years in Salina, Archbishop Weisenburger was surprised again when Pope Francis called him to Tucson in 2017. Archbishop Weisenburger said he’s been just as grateful for his ministry in Arizona, in particular the support he received from his predecessor, Bishop Gerald F. Kicanas, who “was just marvelously helpful to me.”

Each of the dioceses he’s led have come with their own blessings, challenges and ways of living the faith — a distinction Archbishop Weisenburger has come to appreciate. The archbishop said he tries to model his ministry after Pope Francis’ synodal style of leadership, which involves a lot of listening and discernment.

“We tend to think the Church is everywhere the way we live it. What I have found is that while the sacraments and the faith are the same, the practice of the faith varies widely,” Archbishop Weisenburger said. “A bishop’s real job is to enable that ministry to happen well at the parish level, and that’s why he works so closely with his priests.”

“I think that’s how the best of bishops continue following (Pope Francis') example, which really is the example of the early Church," Archbishop Weisenburger continued. "He has reawakened within us something that was there in our Church from the beginning: that really profound listening, which is related to discernment. He does not allow discernment to become crippling, but he empowers that discernment profoundly, he has a vision, and he moves.”

As he looks forward to his years in Detroit, the archbishop said he’s heartened by the devotion of his predecessor, Archbishop Allen H. Vigneron, and the foundation he has left, and sees blessings in the years ahead in southeast Michigan.

He’s particularly excited about the Church’s future, he said, when he speaks to young people about their faith.

“I think young people are asking the best questions. I’m not sure we’re always listening to them, but they’re asking really good questions about the future,” Archbishop Weisenburger said. “They've seen in previous generations the unhappiness, the sense of a lack of meaning and purpose. And they're looking for a life of meaning and purpose."

One way in which that movement can manifest itself is by continuing to promote a robust culture of vocations, he said, so that other young men and women might see in themselves a future of service to the Church — the same future he saw when he first looked in the mirror as an altar server in the 1960s.

“Vocations are a sign of a healthy Church," he continued. "I think we’re beginning to see more young men and young women saying, ‘This is what I’m being called to.’ And it is a purposeful life, and a life of joy and meaning. I think we're on the cusp of something that's going to be a wonderful future, and I'm excited about seeing it unfold in our midst.”

Copy Permalink

Bishops Episcopal transition